Hey folks, another hero of Scottish inventions takes a look at Sir Alexander Fleming, the man who made it possible to fight virus and diseases through Penicillin.

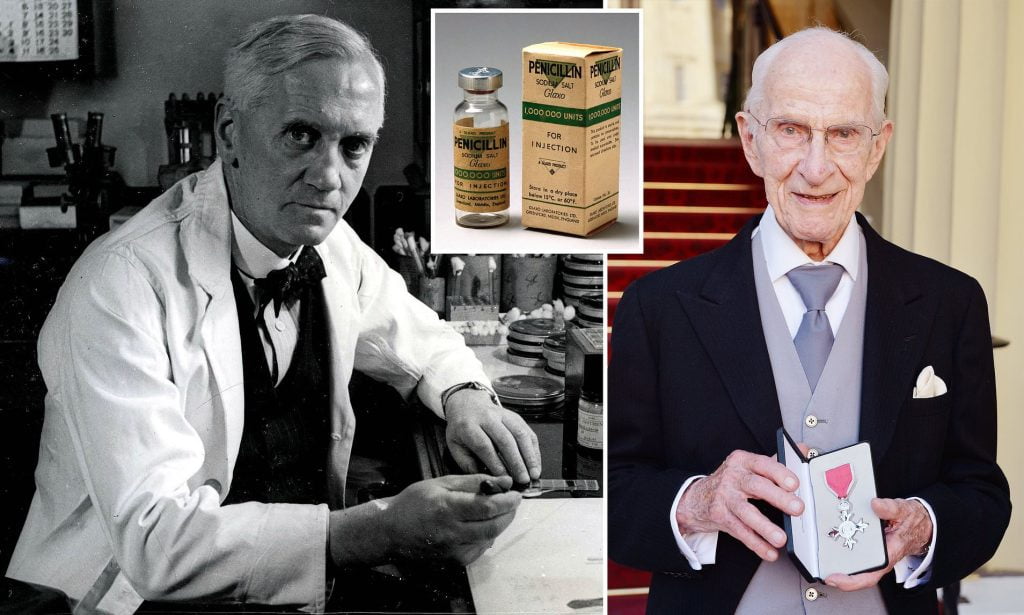

Sir Alexander Fleming FRS FRSE FRCS (6 August 1881 – 11 March 1955) was a Scottish biologist physician microbiologist, and pharmacologist. His best-known discoveries are the enzyme lysozyme in 1923 and the world’s first antibiotic substance benzylpenicillin (Penicillin G) from the mould Penicillium notatum in 1928, for which he shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1945 with Howard Florey and Ernst Boris Chain. He wrote many articles on bacteriology, immunology, and chemotherapy.

An advertisement advertising penicillin’s “miracle cure”.

Fleming was knighted for his scientific achievements in 1944. In 1999, he was named in Time magazine’s list of the 100 Most Important People of the 20th century. In 2002, he was chosen in the BBC’s television poll for determining the 100 Greatest Britons, and in 2009, he was also voted third “greatest Scot” in an opinion poll conducted by STV, behind only Robert Burns and William Wallace.

Early life and education

Born on 6 August 1881 at Lochfield farm near Darvel, in Ayrshire, Scotland, Alexander was the third of four children of farmer Hugh Fleming (1816–1888) from his second marriage to Grace Stirling Morton (1848–1928), the daughter of a neighbouring farmer. Hugh Fleming had four surviving children from his first marriage. He was 59 at the time of his second marriage and died when Alexander was seven.

Fleming went to Loudoun Moor School and Darvel School and earned a two-year scholarship to Kilmarnock Academy before moving to London, where he attended the Royal Polytechnic Institution. After working in a shipping office for four years, the twenty-year-old Alexander Fleming inherited some money from an uncle, John Fleming. His elder brother, Tom, was already a physician and suggested to him that he should follow the same career, and so in 1903, the younger Alexander enrolled at St Mary’s Hospital Medical School in Paddington; he qualified with an MBBS degree from the school with distinction in 1906.

Fleming, who was a private in the London Scottish Regiment of the Volunteer Force from 1900 to 1914, had been a member of the rifle club at the medical school. The captain of the club, wishing to retain Fleming in the team, suggested that he join the research department at St Mary’s, where he became assistant bacteriologist to Sir Almroth Wright, a pioneer in vaccine therapy and immunology. In 1908, he gained a BSc degree with Gold Medal in Bacteriology and became a lecturer at St Mary’s until 1914. Commissioned lieutenant in 1914 and promoted captain in 1917, Fleming served throughout World War I in the Royal Army Medical Corps, and was Mentioned in Dispatches. He and many of his colleagues worked in battlefield hospitals at the Western Front in France. In 1918 he returned to St Mary’s Hospital, where he was elected Professor of Bacteriology of the University of London in 1928. In 1951 he was elected the Rector of the University of Edinburgh for a term of three years.

Research

Work before penicillin

During World War I, Fleming witnessed the death of many soldiers from sepsis resulting from infected wounds. Antiseptics, which were used at the time to treat infected wounds, often worsened the injuries. In an article he submitted for the medical journal The Lancet during World War I, Fleming described an ingenious experiment, which he was able to conduct as a result of his own glass blowing skills, in which he explained why antiseptics were killing more soldiers than infection itself during World War I. Antiseptics worked well on the surface, but deep wounds tended to shelter anaerobic bacteria from the antiseptic agent, and antiseptics seemed to remove beneficial agents produced that protected the patients in these cases at least as well as they removed bacteria, and did nothing to remove the bacteria that were out of reach. Sir Almroth Wright strongly supported Fleming’s findings, but despite this, most army physicians over the course of the war continued to use antiseptics even in cases where this worsened the condition of the patients.

At St Mary’s Hospital Fleming continued his investigations into antibacterial substances. Testing the nasal secretions from a patient with a heavy cold, he found that nasal mucus had an inhibitory effect on bacterial growth. This was the first recorded discovery of lysozyme, an enzyme present in many secretions including tears, saliva, skin, hair and nails as well as mucus. Although he was able to obtain larger amounts of lysozyme from egg whites, the enzyme was only effective against small counts of harmless bacteria, and therefore had little therapeutic potential.

Accidental discovery

Main article: History of penicillin

One sometimes finds, what one is not looking for. When I woke up just after dawn on September 28, 1928, I certainly didn’t plan to revolutionize all medicine by discovering the world’s first antibiotic, or bacteria killer. But I suppose that was exactly what I did.

— Alexander Fleming.

By 1927, Fleming had been investigating the properties of staphylococci. He was already well known from his earlier work and had developed a reputation as a brilliant researcher, but his laboratory was often untidy. On 3 September 1928, Fleming returned to his laboratory having spent August on holiday with his family. Before leaving for his holiday, he had stacked all his cultures of staphylococci on a bench in a corner of his laboratory. On returning, Fleming noticed that one culture was contaminated with a fungus and that the colonies of staphylococci immediately surrounding the fungus had been destroyed, whereas other staphylococci colonies farther away were normal, famously remarking “That’s funny”. Fleming showed the contaminated culture to his former assistant Merlin Pryce, who reminded him, “That’s how you discovered lysozyme.” Fleming grew the mould in pure culture and found that it produced a substance that killed a number of disease-causing bacteria. He identified the mould as being from the genus Penicillium, and, after some months of calling it “mould juice”, named the substance it released penicillin on 7 March 1929. The laboratory in which Fleming discovered and tested penicillin is preserved as the Alexander Fleming Laboratory Museum in St. Mary’s Hospital, Paddington.

He investigated its positive anti-bacterial effect on many organisms and noticed that it affected bacteria such as staphylococci and many other Gram-positive pathogens that cause scarlet fever, pneumonia, meningitis and diphtheria, but not typhoid fever or paratyphoid fever, which is caused by Gram-negative bacteria, for which he was seeking a cure at the time. It also affected Neisseria gonorrhoeae, which causes gonorrhoea, although this bacterium is Gram-negative.

Fleming published his discovery in 1929, in the British Journal of Experimental Pathology, but little attention was paid to his article. Fleming continued his investigations but found that cultivating Penicillium was quite difficult and that after having grown the mould, it was even more difficult to isolate the antibiotic agent. Fleming’s impression was that because of the problem of producing it in quantity, and because its action appeared to be rather slow, penicillin would not be important in treating infection. Fleming also became convinced that penicillin would not last long enough in the human body (in vivo) to kill bacteria effectively. Many clinical tests were inconclusive, probably because it had been used as a surface antiseptic. In the 1930s, Fleming’s trials occasionally showed more promise, but Fleming largely abandoned penicillin work, leaving Howard Florey and Ernst Boris Chain at the Radcliffe Infirmary in Oxford to take up research to mass-produce it, with funds from the U.S. and British governments. They started mass production after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. By D-Day in 1944, enough penicillin had been produced to treat all the wounded in the Allied forces.

Purification and stabilisation

3D-model of benzylpenicillin

In Oxford, Ernst Boris Chain and Edward Abraham were studying the molecular structure of the antibiotic. Abraham was the first to propose the correct structure of penicillin. Shortly after the team published its first results in 1940, Fleming telephoned Howard Florey, Chain’s head of department, to say that he would be visiting within the next few days. When Chain heard that Fleming was coming, he remarked “Good God! I thought he was dead.”

Norman Heatley suggested transferring the active ingredient of penicillin back into the water by changing its acidity. This produced enough of the drug to begin testing on animals. There were many more people involved in the Oxford team, and at one point the entire Dunn School was involved in its production.

After the team had developed a method of purifying penicillin to an effective first stable form in 1940, several clinical trials ensued, and their amazing success inspired the team to develop methods for mass production and mass distribution in 1945.

Fleming was modest about his part in the development of penicillin, describing his fame as the “Fleming Myth” and he praised Florey and Chain for transforming the laboratory curiosity into a practical drug. Fleming was the first to discover the properties of the active substance, giving him the privilege of naming it: penicillin. He also kept, grew, and distributed the original mould for twelve years, and continued until 1940 to try to get help from any chemist who had enough skill to make penicillin. But Sir Henry Harris said in 1998: “Without Fleming, no Chain; without Chain, no Florey; without Florey, no Heatley; without Heatley, no penicillin.”

Antibiotics

Modern antibiotics are tested using a method similar to Fleming’s discovery.

Fleming’s accidental discovery and isolation of penicillin in September 1928 marks the start of modern antibiotics. Before that, several scientists had published or pointed out that mould or Penicillium sp. were able to inhibit bacterial growth, and even to cure bacterial infections in animals. Ernest Duchesne in 1897 in his thesis “Contribution to the study of vital competition in micro-organisms: antagonism between moulds and microbes”, or also Clodomiro Picado Twight whose work at the Institut Pasteur in 1923 on the inhibiting action of fungi of the Penicillin sp. genre in the growth of staphylococci drew little interest from the directors of the Institut at the time. Fleming was the first to push these studies further by isolating the penicillin, and by being motivated enough to promote his discovery at a larger scale.

Fleming also discovered very early that bacteria developed antibiotic resistance whenever too little penicillin was used or when it was used for too short a period. Almroth Wright had predicted antibiotic resistance even before it was noticed during experiments. Fleming cautioned about the use of penicillin in his many speeches around the world. On 26 June 1945, he made the following cautionary statements: “the microbes are educated to resist penicillin and a host of penicillin-fast organisms is bred out … In such cases, the thoughtless person playing with penicillin is morally responsible for the death of the man who finally succumbs to infection with the penicillin-resistant organism. I hope this evil can be averted.” He cautioned not to use penicillin unless there was a properly diagnosed reason for it to be used and that if it were used, never to use too little, or for too short a period, since these are the circumstances under which bacterial resistance to antibiotics develops.

Personal life

Grave of Alexander Fleming in the crypt of St Paul’s Cathedral, London.

On 24 December 1915, Fleming married a trained nurse, Sarah Marion McElroy of Killala, County Mayo, Ireland. Their only child, Robert Fleming (1924–2015), became a general medical practitioner. After his first wife’s death in 1949, Fleming married Dr Amalia Koutsouri-Vourekas, a Greek colleague at St. Mary’s, on 9 April 1953; she died in 1986. Fleming was a Roman Catholic.

From 1921 until his death in 1955, Fleming owned a country home in Barton Mills, Suffolk.

Death

On 11 March 1955, Fleming died at his home in London of a heart attack. His ashes are buried in St Paul’s Cathedral.