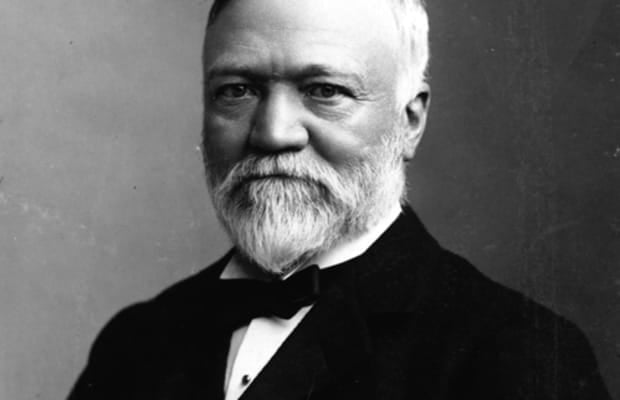

Andrew Carnegie (November 25, 1835 – August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist, and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century and became one of the richest Americans in history. He became a leading philanthropist in the United States and in the British Empire. During the last 18 years of his life, he gave away $350 million (conservatively $65 billion in 2019 dollars, based on percentage of GDP) to charities, foundations, and universities – almost 90 percent of his fortune. His 1889 article proclaiming “The Gospel of Wealth” called on the rich to use their wealth to improve society, and stimulated a wave of philanthropy.

Carnegie was born in Dunfermline, Scotland, and immigrated to the United States with his parents in 1848 at age 12. Carnegie started work as a telegrapher, and by the 1860s had investments in railroads, railroad sleeping cars, bridges, and oil derricks. He accumulated further wealth as a bond salesman, raising money for American enterprise in Europe. He built Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Steel Company, which he sold to J. P. Morgan in 1901 for $303,450,000. It became the U.S. Steel Corporation. After selling Carnegie Steel, he surpassed John D. Rockefeller as the richest American for the next several years.

Carnegie devoted the remainder of his life to large-scale philanthropy, with special emphasis on local libraries, world peace, education, and scientific research. With the fortune he made from business, he built Carnegie Hall in New York, NY, and the Peace Palace and founded the Carnegie Corporation of New York, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Carnegie Institution for Science, Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland, Carnegie Hero Fund, Carnegie Mellon University, and the Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh, among others.

Biography

Andrew Carnegie was born to Margaret Morrison Carnegie and William Carnegie in Dunfermline, Scotland, in a typical weaver’s cottage with only one main room, consisting of half the ground floor, which was shared with the neighbouring weaver’s family. The main room served as a living room, dining room and bedroom. He was named after his paternal grandfather. In 1836, the family moved to a larger house in Edgar Street (opposite Reid’s Park), following the demand for more heavy damask, from which his father benefited. He was educated at the Free School in Dunfermline, which had been a gift to the town by the philanthropist Adam Rolland of Gask.

Carnegie’s maternal uncle, George Lauder, Sr., a Scottish political leader, deeply influenced him as a boy by introducing him to the writings of Robert Burns and historical Scottish heroes such as Robert the Bruce, William Wallace, and Rob Roy. Lauder’s son, also named George Lauder, grew up with Carnegie and would become his business partner. When Carnegie was thirteen, his father had fallen on very hard times as a handloom weaver; making matters worse, the country was in starvation. His mother helped support the family by assisting her brother (a cobbler), and by selling potted meats at her “sweetie shop”, leaving her as the primary breadwinner. Struggling to make ends meet, the Carnegies then decided to borrow money from George Lauder, Sr and move to Allegheny, Pennsylvania, in the United States in 1848 for the prospect of a better life. Carnegie’s migration to America would be his second journey outside Dunfermline – the first being an outing to Edinburgh to see Queen Victoria.

In September 1848, Carnegie arrived with his family at their new prosperous home. Allegheny was rapidly populating in the 1840s, growing from around 10,000 to 21,262 residents. The city was very industrial and produced many products including wool and cotton cloth. The “Made in Allegheny” label used on these and other diversified products was becoming more and more popular. For his father, the promising circumstances still did not provide him with any good fortune. Dealers were not interested in selling his product, and he himself struggled to sell it on his own. Eventually, the father and son both received job offers at the same Scottish-owned cotton mill, Anchor Cotton Mills. Carnegie’s first job in 1848 was as a bobbin boy, changing spools of thread in a cotton mill 12 hours a day, 6 days a week in a Pittsburgh cotton factory. His starting wage was $1.20 per week ($35 by 2019 inflation).

His father quit his position at the cotton mill soon after, returning to his loom and removing him as breadwinner once again. But Carnegie attracted the attention of John Hay, a Scottish manufacturer of bobbins, who offered him a job for $2.00 per week ($59 by 2019 inflation). In his autobiography, Carnegie speaks of his past hardships he had to endure with this new job.

Soon after this Mr John Hay, a fellow Scotch manufacturer of bobbins in Allegheny City needed a boy and asked whether I would not go into his service. I went and received two dollars per week, but at first, the work was even more irksome than the factory. I had to run a small steam-engine and to fire the boiler in the cellar of the bobbin factory. It was too much for me. I found myself night after night, sitting up in bed trying the steam gauges, fearing at one time that the steam was too low and that the workers above would complain that they had not power enough, and at another time that the steam was too high and that the boiler might burst.

Railroads

In 1849, Carnegie became a telegraph messenger boy in the Pittsburgh Office of the Ohio Telegraph Company, at $2.50 per week ($77 by 2019 inflation) following the recommendation of his uncle. He was a hard worker and would memorize all of the locations of Pittsburgh’s businesses and the faces of important men. He made many connections this way. He also paid close attention to his work and quickly learned to distinguish the different sounds the incoming telegraph signals produced. He developed the ability to translate signals by ear, without using the paper slip, and within a year was promoted to the operator. Carnegie’s education and passion for reading was given a boost by Colonel James Anderson, who opened his personal library of 400 volumes to working boys each Saturday night. Carnegie was a consistent borrower and a “self-made man” in both his economic development and his intellectual and cultural development. He was so grateful to Colonel Anderson for the use of his library that he “resolved, if ever wealth came to me, [to see to it] that other poor boys might receive opportunities similar to those for which we were indebted to the nobleman”.His capacity, his willingness for hard work, his perseverance and his alertness soon brought him opportunities.

Starting in 1853, when Carnegie was around 18 years old, Thomas A. Scott of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company employed him as a secretary/telegraph operator at a salary of $4.00 per week ($123 by 2019 inflation). Carnegie accepted the job with the railroad as he saw more prospects for career growth and experience there than with the telegraph company. At age 24, Scott asked Carnegie if he could handle being superintendent of the Western Division of the Pennsylvania Railroad. On December 1, 1859, Carnegie officially became superintendent of the Western Division. Carnegie then hired his sixteen-year-old brother, Tom, to be his personal secretary and telegraph operator. Not only did Carnegie hire his brother, but he also hired his cousin, Maria Hogan, who became the first female telegraph operator in the country. As superintendent Carnegie made a salary of fifteen hundred dollars a year ($43,000 by 2019 inflation). His employment by the Pennsylvania Railroad Company would be vital to his later success. The railroads were the first big businesses in America, and the Pennsylvania was one of the largest of them all. Carnegie learned much about management and cost control during these years, and from Scott in particular.

Scott also helped him with his first investments. Many of these were part of the corruption indulged in by Scott and the Pennsylvania’s president, John Edgar Thomson, which consisted of inside trading in companies that the railroad did business with, or payoffs made by contracting parties “as part of a quid pro quo”. In 1855, Scott made it possible for Carnegie to invest $500 in the Adams Express, which contracted with the Pennsylvania to carry its messengers. The money was secured by his mother’s placing of a $600 mortgage on the family’s $700 home, but the opportunity was available only because of Carnegie’s close relationship with Scott. A few years later, he received a few shares in Theodore Tuttle Woodruff’s sleeping car company, as a reward for holding shares that Woodruff had given to Scott and Thomson, as a payoff. Reinvesting his returns in such inside investments in railroad-related industries: (iron, bridges, and rails), Carnegie slowly accumulated capital, the basis for his later success. Throughout his later career, he made use of his close connections to Thomson and Scott, as he established businesses that supplied rails and bridges to the railroad, offering the two men a stake in his enterprises.

1860–1865: The Civil War

Before the Civil War, Carnegie arranged a merger between Woodruff’s company and that of George Pullman, the inventor of the sleeping car for first-class travel, which facilitated business travel at distances over 500 miles (800 km). The investment proved a success and a source of profit for Woodruff and Carnegie. The young Carnegie continued to work for Pennsylvania’s Tom Scott and introduced several improvements in the service.

In spring 1861, Carnegie was appointed by Scott, who was now Assistant Secretary of War in charge of military transportation, as Superintendent of the Military Railways and the Union Government’s telegraph lines in the East. Carnegie helped open the rail lines into Washington D.C. that the rebels had cut; he rode the locomotive pulling the first brigade of Union troops to reach Washington D.C. Following the defeat of Union forces at Bull Run, he personally supervised the transportation of the defeated forces. Under his organization, the telegraph service rendered efficient service to the Union cause and significantly assisted in the eventual victory. Carnegie later joked that he was “the first casualty of the war” when he gained a scar on his cheek from freeing a trapped telegraph wire.

Defeat of the Confederacy required vast supplies of munitions, as well as railroads (and telegraph lines) to deliver the goods. The war demonstrated how integral the industries were to American success.

Keystone Bridge Company

In 1864, Carnegie was one of the early investors in the Columbia Oil Company in Venango County, Pennsylvania. In one year, the farm yielded over $1,000,000 in cash dividends, and petroleum from oil wells on the property sold profitably. The demand for iron products, such as armour for gunboats, cannons, and shells, as well as a hundred other industrial products, made Pittsburgh a centre of wartime production. Carnegie worked with others in establishing a steel rolling mill, and steel production and control of industry became the source of his fortune. Carnegie had some investments in the iron industry before the war.

After the war, Carnegie left the railroads to devote his energies to the ironworks trade. Carnegie worked to develop several ironworks, eventually forming the Keystone Bridge Works and the Union Ironworks, in Pittsburgh. Although he had left the Pennsylvania Railroad Company, he remained connected to its management, namely Thomas A. Scott and J. Edgar Thomson. He used his connection to the two men to acquire contracts for his Keystone Bridge Company and the rails produced by his ironworks. He also gave the stock to Scott and Thomson in his businesses, and Pennsylvania was his best customer. When he built his first steel plant, he made a point of naming it after Thomson. As well as having good business sense, Carnegie possessed charm and literary knowledge. He was invited to many important social functions, which Carnegie exploited to his advantage.

Carnegie, c. 1878

Carnegie believed in using his fortune for others and doing more than making money. He wrote:

I propose to take an income no greater than $50,000 per annum! Beyond this, I need ever earn, make no effort to increase my fortune, but spend the surplus each year for benevolent purposes! Let us cast aside business forever, except for others. Let us settle in Oxford and I shall get a thorough education, making the acquaintance of literary men. I figure that this will take three years’ active work. I shall pay especial attention to speaking in public. We can settle in London and I can purchase a controlling interest in some newspaper or live review and give the general management of it attention, taking part in public matters, especially those connected with education and improvement of the poorer classes. Man must have no idol and the amassing of wealth is one of the worst species of idolatry! No idol is more debasing than the worship of money! Whatever I engage in I must push inordinately; therefore should I be careful to choose that life which will be the most elevating in its character. To continue much longer overwhelmed by business cares and with most of my thoughts wholly upon the way to make more money in the shortest time must degrade me beyond hope of permanent recovery. I will resign business at thirty-five, but during these ensuing two years I wish to spend the afternoons in receiving instruction and in reading systematically!

Industrialist

1885–1900: Steel empire

Bessemer converter

Carnegie did not want to marry during his mother’s lifetime, instead choosing to take care of her in her illness towards the end of her life. After she died in 1886, the 51-year-old Carnegie married Louise Whitfield, who was 21 years his junior. In 1897, the couple had their only child, a daughter, whom they named after Carnegie’s mother, Margaret.

Carnegie made his fortune in the steel industry, controlling the most extensive integrated iron and steel operations ever owned by an individual in the United States. One of his two great innovations was in the cheap and efficient mass production of steel by adopting and adapting the Bessemer process, which allowed the high carbon content of pig iron to be burnt away in a controlled and rapid way during steel production. Steel prices dropped as a result, and Bessemer steel was rapidly adopted for rails; however, it was not suitable for buildings and bridges.

The second was in his vertical integration of all suppliers of raw materials. In the late 1880s, Carnegie Steel was the largest manufacturer of pig iron, steel rails, and coke in the world, with a capacity to produce approximately 2,000 tons of pig metal per day. In 1883, Carnegie bought the rival Homestead Steel Works, which included an extensive plant served by tributary coal and iron fields, a 425-mile (684 km) long railway, and a line of lake steamships. Carnegie combined his assets and those of his associates in 1892 with the launching of the Carnegie Steel Company.

By 1889, the U.S. output of steel exceeded that of the UK, and Carnegie owned a large part of it. Carnegie’s empire grew to include the J. Edgar Thomson Steel Works in Braddock, (named for John Edgar Thomson, Carnegie’s former boss and president of the Pennsylvania Railroad), Pittsburgh Bessemer Steel Works, the Lucy Furnaces, the Union Iron Mills, the Union Mill (Wilson, Walker & County), the Keystone Bridge Works, the Hartman Steel Works, the Frick Coke Company, and the Scotia ore mines. Carnegie, through Keystone, supplied the steel for and owned shares in the landmark Eads Bridge project across the Mississippi River at St. Louis, Missouri (completed 1874). This project was an important proof-of-concept for steel technology, which marked the opening of a new steel market.

1901: U.S. Steel

In 1901, Carnegie was 66 years of age and considering retirement. He reformed his enterprises into conventional joint stock corporations as preparation for this. John Pierpont Morgan was a banker and America’s most important financial deal maker. He had observed how efficiently Carnegie produced profits. He envisioned an integrated steel industry that would cut costs, lower prices to consumers, produce in greater quantities and raise wages to workers. To this end, he needed to buy out Carnegie and several other major producers and integrate them into one company, thereby eliminating duplication and waste. He concluded negotiations on March 2, 1901, and formed the United States Steel Corporation. It was the first corporation in the world with a market capitalization over $1 billion.

The buyout, secretly negotiated by Charles M. Schwab (no relation to Charles R. Schwab), was the largest such industrial takeover in United States history to date. The holdings were incorporated in the United States Steel Corporation, a trust organized by Morgan, and Carnegie retired from business. His steel enterprises were bought out for $303,450,000.

Carnegie’s share of this amounted to $225.64 million (in 2019, $6.93 billion), which was paid to Carnegie in the form of 5%, 50-year gold bonds. The letter agreeing to sell his share was signed on February 26, 1901. On March 2, the circular formally filing the organization and capitalization (at $1.4 billion – 4 per cent of the U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) at the time) of the United States Steel Corporation actually completed the contract. The bonds were to be delivered within two weeks to the Hudson Trust Company of Hoboken, New Jersey, in trust to Robert A. Franks, Carnegie’s business secretary. There, a special vault was built to house the physical bulk of nearly $230 million worth of bonds.

Scholar and activist

1880–1900

Carnegie continued his business career; some of his literary intentions were fulfilled. He befriended the English poet Matthew Arnold, the English philosopher Herbert Spencer, and the American humorist Mark Twain, as well as being in correspondence and acquaintance with most of the U.S. Presidents, statesmen, and notable writers.

Carnegie constructed commodious swimming-baths for the people of his hometown in Dunfermline in 1879. In the following year, Carnegie gave £8,000 for the establishment of a Dunfermline Carnegie Library in Scotland. In 1884, he gave $50,000 to Bellevue Hospital Medical College (now part of New York University Medical Center) to found a histological laboratory, now called the Carnegie Laboratory.

In 1881, Carnegie took his family, including his 70-year-old mother, on a trip to the United Kingdom. They toured Scotland by coach, and enjoyed several receptions en route. The highlight was a return to Dunfermline, where Carnegie’s mother laid the foundation stone of a Carnegie library which he funded. Carnegie’s criticism of British society did not mean dislike; on the contrary, one of Carnegie’s ambitions was to act as a catalyst for a close association between English-speaking peoples. To this end, in the early 1880s in partnership with Samuel Storey, he purchased numerous newspapers in England, all of which were to advocate the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of “the British Republic”. Carnegie’s charm, aided by his wealth, afforded him many British friends, including Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone.

In 1886, Carnegie’s younger brother Thomas died at age 43. While owning steel works, Carnegie had purchased at low cost the most valuable of the iron ore fields around Lake Superior. The same year Carnegie became a figure of controversy. Following his tour of the UK, he wrote about his experiences in a book entitled An American Four-in-hand in Britain.

Carnegie, right, with James Bryce, 1st Viscount Bryce in 1886

Although actively involved in running his many businesses, Carnegie had become a regular contributor to numerous magazines, most notably The Nineteenth Century, under the editorship of James Knowles, and the influential North American Review, led by editor Lloyd Bryce.

In 1886, Carnegie wrote his most radical work to date, entitled Triumphant Democracy. Liberal in its use of statistics to make its arguments, the book argued his view that the American republican system of government was superior to the British monarchical system. It gave a highly favorable and idealized view of American progress and criticized the British royal family. The cover depicted an upended royal crown and a broken scepter. The book created considerable controversy in the UK. The book made many Americans appreciate their country’s economic progress and sold over 40,000 copies, mostly in the US.

In 1889, Carnegie published “Wealth” in the June issue of the North American Review. After reading it, Gladstone requested its publication in England, where it appeared as “The Gospel of Wealth” in the Pall Mall Gazette. Carnegie argued that the life of a wealthy industrialist should comprise two parts. The first part was the gathering and the accumulation of wealth. The second part was for the subsequent distribution of this wealth to benevolent causes. Philanthropy was key to making life worthwhile.

Carnegie was a well-regarded writer. He published three books on travel.

Anti-imperialism

While Carnegie did not comment on British imperialism, he strongly opposed the idea of American colonies. He opposed the annexation of the Philippines almost to the point of supporting William Jennings Bryan against McKinley in 1900. In 1898, Carnegie tried to arrange for independence for the Philippines. As the end of the Spanish–American War neared, the United States bought the Philippines from Spain for $20 million. To counter what he perceived as imperialism on the part of the United States, Carnegie personally offered $20 million to the Philippines so that the Filipino people could buy their independence from the United States. However, nothing came of the offer. In 1898 Carnegie joined the American Anti-Imperialist League, in opposition to the U.S. annexation of the Philippines. Its membership included former presidents of the United States Grover Cleveland and Benjamin Harrison and literary figures like Mark Twain.

1901–1919: Philanthropist

Main articles: Carnegie library, Carnegie Corporation of New York, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Carnegie Institution for Science, Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland, Carnegie United Kingdom Trust, Carnegie Hero Fund, Carnegie Mellon University, and Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh

See also: Carnegie Hall, Tuskegee Institute, and Hooker telescope

Andrew Carnegie’s philanthropy. Puck magazine cartoon by Louis Dalrymple, 1903

Carnegie spent his last years as a philanthropist. From 1901 forward, public attention was turned from the shrewd business acumen which had enabled Carnegie to accumulate such a fortune, to the public-spirited way in which he devoted himself to utilizing it on philanthropic projects. He had written about his views on social subjects and the responsibilities of great wealth in Triumphant Democracy (1886) and the Gospel of Wealth (1889). Carnegie bought Skibo Castle in Scotland and made his home partly there and partly in his New York mansion located at 2 East 91st Street at Fifth Avenue. The building was completed in late 1902, and he lived there until his death in 1919. His wife Louise continued to live there until her death in 1946.

The building is now used as the Cooper-Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, part of the Smithsonian Institution. The surrounding neighborhood on Manhattan’s Upper East Side has come to be called Carnegie Hill. The mansion was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1966.

Carnegie devoted the rest of his life to providing capital for purposes of public interest and social and educational advancement. He saved letters of appreciation from those he helped in a desk drawer labeled “Gratitude and Sweet Words.”

Carnegie Hall, NY

He was a powerful supporter of the movement for spelling reform, as a means of promoting the spread of the English language.[28] His organization, the Simplified Spelling Board,[50] created the Handbook of Simplified Spelling, which was written wholly in reformed spelling.[51][52]

3,000 public libraries

Among his many philanthropic efforts, the establishment of public libraries throughout the United States, Britain, Canada and other English-speaking countries was especially prominent. In this special driving interest of his, Carnegie was inspired by meetings with philanthropist Enoch Pratt (1808–1896). The Enoch Pratt Free Library (1886) of Baltimore, Maryland, impressed Carnegie deeply; he said, “Pratt was my guide and inspiration.”

Carnegie turned over management of the library project by 1908 to his staff, led by James Bertram (1874–1934).[53] The first Carnegie library opened in 1883 in Dunfermline. His method was to provide funds to build and equip the library, but only on condition that the local authority matched that by providing the land and a budget for operation and maintenance.

To secure local interest, in 1885, he gave $500,000 to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania for a public library, and in 1886, he gave $250,000 to Allegheny City, Pennsylvania for a music hall and library; and $250,000 to Edinburgh for a free library. In total, Carnegie funded some 3,000 libraries, located in 47 US states, and also in Canada, Britain, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, the West Indies, and Fiji. He also donated £50,000 to help set up the University of Birmingham in 1899.

As Van Slyck (1991) showed, during the last years of the 19th century, there was the increasing adoption of the idea that free libraries should be available to the American public. But the design of such libraries was the subject of prolonged and heated debate. On one hand, the library profession called for designs that supported efficiency in administration and operation; on the other, wealthy philanthropists favoured buildings that reinforced the paternalistic metaphor and enhanced civic pride. Between 1886 and 1917, Carnegie reformed both library philanthropy and library design, encouraging a closer correspondence between the two.

Investing in education

Carnegie Mellon University

In 1900, Carnegie gave $2 million to start the Carnegie Institute of Technology (CIT) at Pittsburgh and the same amount in 1902 to found the Carnegie Institution at Washington, D.C. He later contributed more to these and other schools. CIT is now known as Carnegie Mellon University after it merged with the Mellon Institute of Industrial Research. Carnegie also served on the Boards of Cornell University and Stevens Institute of Technology.

In 1911, Carnegie became a sympathetic benefactor to George Ellery Hale, who was trying to build the 100-inch (2.5 m) Hooker Telescope at Mount Wilson, and donated an additional ten million dollars to the Carnegie Institution with the following suggestion to expedite the construction of the telescope: “I hope the work at Mount Wilson will be vigorously pushed because I am so anxious to hear the expected results from it. I should like to be satisfied before I depart, that we are going to repay to the old land some part of the debt we owe them by revealing more clearly than ever to them the new heavens.” The telescope saw first light on November 2, 1917, with Carnegie still alive.

Pittencrieff Park, Dunfermline

In 1901, in Scotland, he gave $10 million to establish the Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland. It was created by a deed which he signed on June 7, 1901, and it was incorporated by Royal Charter on August 21, 1902. The establishing gift of $10 million was then an unprecedented sum: at the time, total government assistance to all four Scottish universities was about £50,000 a year. The aim of the Trust was to improve and extend the opportunities for scientific research in the Scottish universities and to enable the deserving and qualified youth of Scotland to attend a university. He was subsequently elected Lord Rector of University of St. Andrews in December 1901 and formally installed as such in October 1902, serving until 1907. He also donated large sums of money to Dunfermline, the place of his birth. In addition to a library, Carnegie also bought the private estate which became Pittencrieff Park and opened it to all members of the public, establishing the Carnegie Dunfermline Trust to benefit the people of Dunfermline. A statue of him stands there today.

He gave a further $10 million in 1913 to endow the Carnegie United Kingdom Trust, a grant-making foundation. He transferred to the trust the charge of all his existing and future benefactions, other than university benefactions in the United Kingdom. He gave the trustees a wide discretion, and they inaugurated a policy of financing rural library schemes rather than erecting library buildings, and of assisting the musical education of the people rather than granting organs to churches.

Carnegie with African-American leader Booker T. Washington (front row, center) in 1906 while visiting Tuskegee Institute

In 1901, Carnegie also established large pension funds for his former employees at Homestead and, in 1905, for American college professors. The latter fund evolved into TIAA-CREF. One critical requirement was that church-related schools had to sever their religious connections to get his money.

His interest in music led him to fund construction of 7,000 church organs. He built and owned Carnegie Hall in New York City.

Carnegie was a large benefactor of the Tuskegee Institute for African-American education under Booker T. Washington. He helped Washington create the National Negro Business League.

April 1905

In 1904, he founded the Carnegie Hero Fund for the United States and Canada (a few years later also established in the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Norway, Sweden, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark, and Germany) for the recognition of deeds of heroism. Carnegie contributed $1,500,000 in 1903 for the erection of the Peace Palace at The Hague; and he donated $150,000 for a Pan-American Palace in Washington as a home for the International Bureau of American Republics.

Carnegie was honored for his philanthropy and support of the arts by initiation as an honorary member of Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia fraternity on October 14, 1917, at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, Massachusetts. The fraternity’s mission reflects Carnegie’s values by developing young men to share their talents to create harmony in the world.

By the standards of 19th century tycoons, Carnegie was not a particularly ruthless man but a humanitarian with enough acquisitiveness to go in the ruthless pursuit of money. “Maybe with the giving away of his money,” commented biographer Joseph Wall, “he would justify what he had done to get that money.”

To some, Carnegie represents the idea of the American dream. He was an immigrant from Scotland who came to America and became successful. He is not only known for his successes but his enormous amounts of philanthropist works, not only to charities but also to promote democracy and independence to colonized countries.

Death

Carnegie died on August 11, 1919, in Lenox, Massachusetts, at his Shadow Brook estate, of bronchial pneumonia. He had already given away $350,695,653 (approximately $76.9 billion, adjusted to 2015 share of GDP figures) of his wealth. After his death, his last $30,000,000 was given to foundations, charities, and to pensioners. He was buried at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Sleepy Hollow, New York. The gravesite is located on the Arcadia Hebron plot of land at the corner of Summit Avenue and Dingle Road. Carnegie is buried only a few yards away from union organizer Samuel Gompers, another important figure of the industry in the Gilded Age.

Andrew Carnegie was definitely one of the most influential Scots… if not the most influential Scot… in world history.

The Old Scona library building in Edmonton the city in Alberta Canada where I grew up and also the oldest public library building in Edmonton started out as a Carnegie library.

Thanks, mate, yes he left a great legacy all over the World a special man, hope you are well Christopher, stay safe mate.