The Battle of Brunanburh was fought in 937 between Æthelstan, King of England, and an alliance of Olaf Guthfrithson, King of Dublin; Constantine II, King of Scotland, and Owain, King of Strathclyde. The battle is often cited as the point of origin for English nationalism: historians such as Michael Livingston argue that “the men who fought and died on that field forged a political map of the future that remains [in modernity], arguably making the Battle of Brunanburh one of the most significant battles in the long history not just of England, but of the whole of the British Isles.”

Following an unchallenged invasion of Scotland by Æthelstan in 934, possibly launched because Constantine had violated a peace treaty, it became apparent that Æthelstan could be defeated only by an alliance of his enemies. Olaf led Constantine and Owen in the alliance. In August 937 Olaf and his army sailed from Dublin to join forces with Constantine and Owen, but the invaders were routed in the battle against Æthelstan. The poem Battle of Brunanburh in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recounts that there were “never yet as many people killed before this with sword’s edge … since the east Angles and Saxons came up over the broad sea”.

Æthelstan’s victory preserved the unity of England. The historian Æthelweard wrote around 975 that “[t]he fields of Britain were consolidated into one, there was peace everywhere, and abundance of all things”. Alfred Smyth has called the battle “the greatest single battle in Anglo-Saxon history before Hastings”. The site of the battle is unknown; many possible locations have been proposed by scholars.

Background.

After Æthelstan defeated the Vikings at York in 927, King Constantine of Scotland, King Hywel Dda of Deheubarth, Ealdred I of Bamburgh, and King Owen I of Strathclyde (or Morgan ap Owain of Gwent) accepted Æthelstan’s overlordship at Eamont, near Penrith.[a] Æthelstan became King of England and there was peace until 934.

Æthelstan invaded Scotland with a large military and naval force in 934. Although the reason for this invasion is uncertain, John of Worcester stated that the cause was Constantine’s violation of the peace treaty made in 927. Æthelstan evidently travelled through Beverley, Ripon, and Chester-le-Street. The army harassed the Scots up to Kincardineshire and the navy up to Caithness, but Æthelstan’s force was never engaged.

Following the invasion of Scotland, it became apparent that Æthelstan could only be defeated by an allied force of his enemies. The leader of the alliance was Olaf Guthfrithson, King of Dublin, joined by Constantine II, King of Scotland and Owen, King of Strathclyde. (According to John of Worcester, Constantine was Olaf’s father-in-law.) Though they had all been enemies in living memory, historian Michael Livingston points out that “they had agreed to set aside whatever political, cultural, historical, and even religious differences they might have had in order to achieve one common purpose: to destroy Æthelstan”.

In August 937, Olaf sailed from Dublin with his army to join forces with Constantine and Owen and in Livingston’s opinion this suggests that the battle of Brunanburh occurred in early October of that year. According to Paul Cavill, the invading armies raided Mercia, from which Æthelstan obtained Saxon troops as he travelled north to meet them. Michael Wood wrote that no source mentions any intrusion into Mercia. According to medieval chroniclers such as John of Worcester and Symeon of Durham, the invaders entered the Humber with a large fleet, although the reliability of these sources is disputed by advocates of an invasion from the west coast of England.

Livingston thinks that the invading armies entered England in two waves, Constantine and Owen coming from the north, possibly engaging in some skirmishes with Æthelstan’s forces as they followed the Roman road across the Lancashire plains between Carlisle and Manchester, with Olaf’s forces joining them on the way. Livingston speculates that the battle site at Brunanburh was chosen in agreement with Æthelstan, on which “there would be one fight, and to the victor went England”.

Battle.

Documents with accounts of the battle include the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the writings of Anglo-Norman historian William of Malmesbury and the Annals of Clonmacnoise. In Snorri Sturluson’s Egils saga, the antihero, mercenary, berserker, and skald, Egill Skallagrimsson, served as a trusted warrior for Æthelstan. It has been suggested that the account in Egil’s Saga is unreliable. Sagas have more than once placed their hero in a famous battle and then embellished it with a series of literary mechanisms.

The main source of information about the battle is the praise-poem Battle of Brunanburh in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. After travelling north through Mercia, Æthelstan, his brother Edmund, and the combined Saxon army from Wessex and Mercia met the invading armies and attacked them. In a battle that lasted all day, the Saxons fought the invaders and finally forced them to break up and flee.There was probably a prolonged period of hard fighting before the invaders were finally defeated. According to the poem, the Saxons “split the shield-wall” and “hewed battle shields with the remnants of hammers … [t]here lay many a warrior by spears destroyed; Northern men shot over shield, likewise Scottish as well, weary, war sated”. Wood states that all large battles were described in this manner, so the description in the poem is not unique to Brunanburh.

Æthelstan and his army pursued the invaders until the end of the day, slaying great numbers of enemy troops. The poem states that “they pursued the hostile people … hew[ing] the fugitive grievously from behind with swords sharp from the grinding”. Olaf fled and sailed back to Dublin with the remnants of his army and Constantine escaped to Scotland; Owen’s fate is not mentioned. The poem states that the Northmen “[d]eparted … in nailed ships” and “sought Dublin over the deep water, leaving Dinges mere to return to Ireland, ashamed in spirit”. The poem records that Æthelstan and Edmund victoriously returned to Wessex, stating that “the brothers, both together, King and Prince, sought their home, West-Saxon land, exultant from battle.”

It is universally agreed by scholars that the invaders were routed by the Saxons. According to the Chronicle, “countless of the army” died in the battle and there were “never yet as many people killed before this with sword’s edge … since from the east Angles and Saxons came up over the broad sea”. The Annals of Ulster describe the battle as “great, lamentable and horrible” and record that “several thousands of Norsemen … fell”. Among the casualties were five kings and seven earls from Olaf’s army. The poem records that Constantine lost several friends and family members in the battle, including his son.The largest list of those killed in the battle is contained in the Annals of Clonmacnoise, which names several kings and princes. A large number of Saxons also died in the battle, including two of Æthelstan’s cousins, Ælfwine and Æthelwine.

Medieval sources.

The battle of Brunanburh is mentioned or alluded to in over forty Anglo-Saxon, Irish, Welsh, Scottish, Norman and Norse medieval texts.

One of the earliest and most informative sources is the Old English poem Battle of Brunanburh in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (version A), which was written within two decades of the battle. The poem relates that Æthelstan and Edmund’s army of West Saxons and Mercians fought at Brunanburh against the Vikings under Anlaf (i.e. Olaf Guthfrithson) and the Scots under Constantine. After a fierce battle lasting all day, five young kings, seven of Anlaf’s earls, and countless others were killed in the greatest slaughter since the Anglo-Saxon invasions. Anlaf and a small band of men escaped by ship over Dingesmere to Dublin. Constantine’s son was killed, and Constantine fled home.

Another very early source, the Irish Annals of Ulster, calls the battle “a huge war, lamentable and horrible”. It notes Anlaf’s return to Dublin with a few men the following year, associated with an event in the spring.

In its only entry for 937, the mid/late 10th-century Welsh chronicle Annales Cambriae laconically states “war at Brune”.

Æthelweard’s Chronicon (ca. 980) says that the battle at “Brunandune” was still known as “the great war” to that day, and no enemy fleet had attacked the country since.

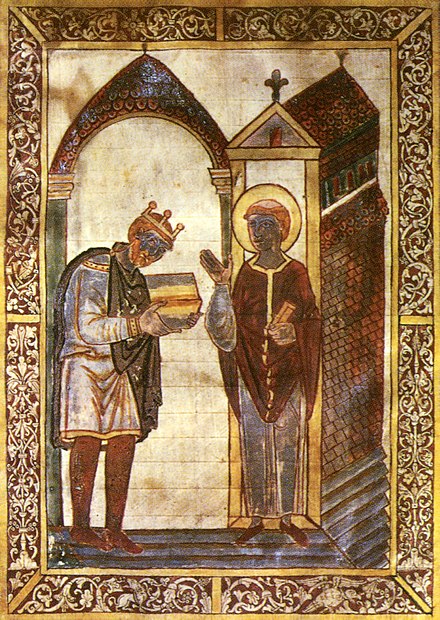

Eadmer of Canterbury’s Vita Odonis (very late 11th century) is one of at least six medieval sources to recount Oda of Canterbury’s involvement in a miraculous restitution of Æthelstan’s sword at the height of the battle.

William Ketel’s De Miraculis Sancti Joannis Beverlacensis (early 12th century) relates how, in 937, Æthelstan left his army on his way north to fight the Scots at Brunanburh, and went to visit the tomb of Bishop John at Beverley to ask for his prayers in the forthcoming battle. In thanksgiving for his victory Æthelstan gave certain privileges and rights to the church at Beverley.

According to Symeon of Durham’s Libellus de exordio (1104–15):

…in the year 937 of the Lord´s Nativity, at Wendune which is called by another name Et Brunnanwerc or Brunnanbyrig, he [Æthelstan] fought against Anlaf, son of former king Guthfrith, who came with 615 ships and had with him the help of the Scots and the Cumbrians.

John of Worcester’s Chronicon ex chronicis (early 12th century) was an influential source for later authors and compilers. It corresponds closely to the description of the battle in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, but adds that:

Anlaf, the pagan king of the Irish and many other islands, incited by his father-in-law Constantine, king of the Scots, entered the mouth of the River Humber with a strong fleet.

Another influential work, Gesta regum Anglorum by William of Malmesbury (1127) adds the detail that Æthelstan “purposely held back”, letting Anlaf advance “far into England”. Michael Wood argues that, in a twelfth-century context, “far into England” could mean anywhere in southern Northumbria or the North Midlands. William of Malmesbury further states that Æthelstan raised 100,000 soldiers. He is at variance with Symeon of Durham in calling Anlaf “son of Sihtric” and asserting that Constantine himself had been slain.

Henry of Huntingdon’s Historia Anglorum (1133) adds the detail that Danes living in England had joined Anlaf’s army. Michael Wood argues that this, together with a similar remark in the Annals of Clonmacnoise, suggests that Anlaf and his allies had established themselves in a centre of Anglo-Scandinavian power prior to the battle.

The mid-12th century text Estoire des Engleis, by the Anglo-Norman chronicler Geoffrey Gaimar, says that Æthelstan defeated the Scots, men of Cumberland, Welsh and Picts at “Bruneswerce”.

The Chronica de Mailros (1173–4) repeats Symeon of Durham’s information that Anlaf arrived with 615 ships, but adds that he entered the mouth of the river Humber.

Egil’s Saga is an Icelandic saga written in Old Norse in 1220–40, which recounts a battle at “Vínheidi” (Vin-heath) by “Vínuskóga” (Vin-wood); it is generally accepted that this refers to the Battle of Brunanburh. Egil’s Saga contains information not found in other sources, such as military engagements prior to the battle, Æthelstan’s use of Viking mercenaries, the topology of the battlefield, the position of Anlaf’s and Æthelstan’s headquarters, and the tactics and unfolding of events during the battle. Historians such as Sarah Foot argue that Egil’s Saga may contain elements of truth but is not a historically reliable narrative.

Pseudo-Ingulf’s Ingulfi Croylandensis Historia (ca. 1400) recounts that:

the Danes of Northumbria and Norfolk entered into a confederacy [against Æthelstan], which was joined by Constantine, king of the Scots, and many others; on which [Æthelstan] levied an army and led it into Northumbria. On his way, he was met by many pilgrims returning homeward from Beverley… [Æthelstan] offered his poniard upon the holy altar [at Beverley], and made a promise that, if the lord would grant him victory over his enemies, he would redeem the said poniard at a suitable price, which he accordingly did…. In the battle which was fought on this occasion there fell Constantine, king of Scots, and five other kings, twelve earls, and an infinite number of the lower classes, on the side of the barbarians.

— Ingulf 1908, p. 58

Although Pseudo-Ingulf may have had access to genuine documents at Croyland Abbey, he is not considered to be a reliable source.

The Annals of Clonmacnoise (an early medieval Irish chronicle of unknown date that survives only in an English translation from 1627) states that:

Awley [i.e. Anlaf], with all the Danes of Dublin and north part of Ireland, departed and went over seas. The Danes that departed from Dublin arrived in England, & by the help of the Danes of that kingdom, they gave battle to the Saxons on the plaines of othlyn, where there was a great slaughter of Normans and Danes.

The Annals of Clonmacnoise records 34,800 Viking and Scottish casualties, including Ceallagh the prince of Scotland (Constantine’s son) and nine other named men.

Aftermath.

Æthelstan’s victory prevented the dissolution of England, but it failed to unite the island: Scotland and Strathclyde remained independent. Foot writes that “[e]xaggerating the importance of this victory is difficult”. Livingston writes that the battle was “the moment when Englishness came of age” and “one of the most significant battles in the long history not just of England but of the whole of the British isles”. The battle was called “the greatest single battle in Anglo-Saxon history before the Hastings” by Alfred Smyth, who nonetheless says its consequences beyond Æthelstan’s reign have been overstated.

Alex Woolf describes it as a pyrrhic victory for Æthelstan: the campaign against the northern alliance ended in a stalemate, his control of the north declined, and after he died Olaf acceded to the Kingdom of Northumbria without resistance. In 954 however the Norse lost their territory in York and Northumbria, with the death of Eric Bloodaxe.

Æthelstan’s ambition to unite the island had failed; the Kingdoms of Scotland and Strathclyde regained their independence, and Great Britain remained divided for centuries to come, Celtic north from Anglo-Saxon south. Æthelweard, writing in the late 900s, said that the battle was “still called the ‘great battle’ by the common people” and that “[t]he fields of Britain were consolidated into one, there was peace everywhere, and abundance of all things”.

Location.

The Brackenwood golf course at Bebington, Wirral

The location of the battlefield is unknown and has been the subject of lively debate among historians since at least the 17th century. Over forty locations have been proposed, from the southwest of England to Scotland, although most historians agree that a location in northern England is the most plausible.

Wirral Archaeology, a local volunteer group, believes that it may have identified the site of the battle near Bromborough on the Wirral. They found a field with a heavy concentration of artifacts which may be a result of metal working in a tenth-century army camp. The location of the field is being kept secret to protect it from nighthawks. As of 2020, they are seeking funds to pursue their research further. The military historian Michael Livingston argues in his 2021 book Never Greater Slaughter that Wirral Archaeology’s case for Bromborough is conclusive, but this claim is criticised in a review of the book by Thomas Williams. He accepts that Bromborough is the only surviving place name which definitely originates in Old English Brunanburh, but says that there could have been others. He comments that evidence of military metal working is unsurprising in an area of Viking activity: it is not evidence for a battle, let alone any particular battle.

The medieval texts employ a plethora of alternative names for the site of the battle, which historians have attempted to link to known places. The earliest relevant document is the “Battle of Brunanburh” poem in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (version A), written within two decades of the battle, which names the battlefield location as “ymbe Brunanburh” (around Brunanburh) and says that the fleeing Norsemen set out upon “Dingesmere” for Dublin. Many other medieval sources contain variations on the name Brunanburh, such as Brune, Brunandune, Et Brunnanwerc, Bruneford, Cad Dybrunawc Duinbrunde and Brounnyngfelde.

It is thought that the recurring element Brun- could be a personal name, a river name, or the Old English or Old Norse word for a spring or stream. Less mystery surrounds the suffixes –burh/–werc, -dun, -ford and –feld, which are the Old English words for a fortification, low hill, ford, and open land respectively.

Ancient artesian spring at Barton-upon-Humber

Not all the place-names contain the Brun- element, however. Symeon of Durham (early 12th C) gives the alternative name Weondune (or Wendune) for the battle site, while the Annals of Clonmacnoise say the battle took place on the “plaines of othlyn” Egil’s Saga names the locations Vínheiðr and Vínuskóga.

Few medieval texts refer to a known place, although the Humber estuary is mentioned by several sources. John of Worcester’s Chronicon (early 12th C), Symeon of Durham’s Historia Regum (mid-12th C), the Chronicle of Melrose (late 12th C) and Robert Mannyng of Brunne’s Chronicle (1338) all state that Olaf’s fleet entered the mouth of the Humber, while Robert of Gloucester’s Metrical Chronicle (late 13th C) says the invading army arrived “south of the Humber”. Peter of Langtoft’s Chronique (ca. 1300) states the armies met at “Bruneburgh on the Humber”, while Robert Mannyng of Brunne’s Chronicle (1338) claims the battle was fought at “Brunesburgh on Humber”. Pseudo-Ingulf (ca. 1400) says that as Æthelstan led his army into Northumbria (i.e. north of the Humber) he met on his way many pilgrims coming home from Beverley. Hector Boece’s Historia (1527) claims that the battle was fought by the River Ouse, which flows into the Humber estuary.

Few other geographical hints are contained in the medieval sources. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recounts that the invaders fled from the battlefield over Dingesmere to regain their ships, so a location near a river or the coast is indicated.

Egil’s Saga contains more detailed topographical information than any of the other medieval texts, although its usefulness as historical evidence is disputed. According to this account, Olaf’s army occupied an unnamed fortified town north of a heath, with large inhabited areas nearby. Æthelstan’s camp was pitched to the south of Olaf, between a river on one side and a forest on raised ground on the other, to the north of another unnamed town at several hours’ ride from Olaf’s camp.

Many sites have been suggested, including:

- Bromborough on the Wirral[b]

- Barnsdale, South Yorkshire [c]

- Brinsworth, South Yorkshire[d]

- Bromswold [e]

- Burnley [f]

- Burnswark, situated near Lockerbie in southern Scotland[g]

- Lanchester, County Durham [h]

- Hunwick in County Durham[i]

- Londesborough and Nunburnholme, East Riding of Yorkshire.

- Heysham, Lancashire [104]

- Barton-upon-Humber in North Lincolnshire[j]

- Little Weighton, East Riding of Yorkshire.