Hi folks, this is a fascinating part of Scottish History. Please enjoy and come back for more.

Earl of Surrey

Lord Thomas Howard

Baron Dacre

Sir Edward Stanley

Marmaduke Constable James IV †

Lord Home

Earl of Montrose †

Earl of Bothwell †

Earl of Lennox †

Earl of Argyll †

Strength

26,000 30,000–40,000

Casualties and losses

1,500[1] 5,000–17,000[2][3]

Location within Northern England

Date 9 September 1513

Location Near Branxton, Northumberland, England

Result English victory

War of the League of Cambrai

Anglo-Scottish Wars

or occasionally Branxton (Brainston Moor was military combat in the War of the League of Cambrai between the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland, resulting in an English victory. The battle was fought in Branxton in the county of Northumberland in northern England on 9 September 1513, between an invading Scots army under King James IV and an English army commanded by the Earl of Surrey. In terms of troop numbers, it was the largest battle fought between the two kingdoms. James IV was killed in the battle, becoming the last monarch from the British Isles to die in battle.

This conflict began when James IV, King of Scots declared war on England to honour the Auld Alliance with France by diverting Henry VIII’s English troops from their campaign against the French king Louis XII. Henry VIII had also opened old wounds by claiming to be the overlord of Scotland, which angered the Scots and their King. At this time, England was involved as a member of the “Catholic League” in the War of the League of Cambrai—defending Italy and the Pope from the French (see Italian Wars).

Pope Leo X, already a signatory to the anti-French Treaty of Mechlin, sent a letter to James threatening him with ecclesiastical censure for breaking his peace treaties with England on 28 June 1513, and subsequently, James was excommunicated by Cardinal Christopher Bainbridge. James also summoned sailors and sent the Scottish navy, including the Great Michael, to join the ships of Louis XII of France.

Henry was in France with Emperor Maximilian at the siege of Thérouanne. The Scottish Lyon King of Arms brought James IV’s letter of 26 July to him. James asked him to desist from attacking France in breach of their treaty. Henry’s exchange with Islay Herald or the Lyon King on 11 August at his tent at the siege was recorded. The Herald declared that Henry should abandon his efforts against the town and go home. Angered, Henry said that James had no right to summon him, and ought to be England’s ally, as James was married to his (Henry’s) sister, Margaret. He declared:

And now, for a conclusion, recommend me to your master and tell him if he is so hardy to invade my realm or cause to enter one foot of my ground I shall make him as weary of his part as ever was a man that began any such business. And one thing I ensure him by the faith that I have to the Crown of England and by the word of a King, there shall never King nor Prince make peace with me that ever his part shall be in it. Moreover, fellow, I care for nothing but for misentreating of my sister, that would God she were in England on a condition she cost the Schottes King, not a penny.

Henry also replied by letter on 12 August, writing that James was mistaken and that any of his attempts on England would be resisted. Using the pretext of revenge for the murder of Robert Kerr, a Warden of the Scottish East March who had been killed by John “The Bastard” Heron in 1508, James invaded England with an army of about 30,000 men. However, both sides had been making lengthy preparations for this conflict. Henry VIII had already organised an army and artillery in the north of England to counter the expected invasion. Some of the guns had been returned to use against the Scots by Margaret of Austria, Duchess of Savoy. A year earlier, Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey, had been appointed Lieutenant-General of the army of the north and was issued with banners of the Cross of St George and the Red Dragon of Wales. Only a small number of the light horsemen of the Scottish border had been sent to France. A northern army was maintained with artillery and its expense account starts on 21 July 1513. The first captains were recruited in Lambeth. Many of these soldiers wore green and white Tudor colours. Surrey marched to Doncaster in July and then Pontefract, where he assembled more troops from northern England.

On 18 August, five cannon brought down from Edinburgh Castle to the Netherbow Port at St Mary’s Wynd for the invasion set off towards England dragged by borrowed oxen. On 19 August two ‘gross culverins’, four ‘culverins pickmoyance’ and six (mid-sized) ‘culverins moyane’ followed with the gunner Robert Borthwick and master carpenter John Drummond. The King himself set off that night with two hastily prepared standards of St Margaret and St Andrew.

Catherine of Aragon was Regent in England. On 27 August, she issued warrants for the property of all Scotsmen in England to be seized. On hearing of the invasion on 3 September, she ordered Thomas Lovell to raise an army in the Midland counties.

In keeping with his understanding of the medieval code of chivalry, King James sent a notice to the English, one month in advance, of his intent to invade. This gave the English time to gather an army and to retrieve the banner of Saint Cuthbert from Durham Cathedral, a banner which had been carried by the English in victories against the Scots in 1138 and 1346. After a muster on the Burgh Muir of Edinburgh, the Scottish host moved to Ellemford, to the north of Duns, and camped to wait for Angus and Home. The Scottish army then crossed the River Tweed near Coldstream. On 24 August, James IV held a council or parliament at Twiselhaugh and made a proclamation for the benefit of the heirs of anyone killed during this invasion. By 29 August Norham Castle was taken and partly demolished. The Scots moved south, capturing the castles of Etal and Ford.

A later Scottish chronicle writer, Robert Lindsay of Pitscottie, tells the story that James wasted valuable time at Ford enjoying the company of Elizabeth, Lady Heron and her daughter. Edward Hall says that Lady Heron was a prisoner (in Scotland), and negotiated with James IV and the Earl of Surrey her own release and that Ford Castle would not be demolished for an exchange of prisoners. The English herald, Rouge Croix, came to Ford to appoint a place for battle on 4 September, with extra instructions that any Scottish heralds who were sent to Surrey were to be met where they could not view the English forces. Raphael Holinshed’s story is that a part of the Scottish army returned to Scotland, and the rest stayed at Ford waiting for Norham to surrender and debating their next move. James IV wanted to fight and considered moving to assault Berwick-upon-Tweed, but the Earl of Angus spoke against this and said that Scotland had done enough for France. James sent Angus home, and according to Holinshed, the Earl burst into tears and left, leaving his two sons, the Master of Angus and Glenbervie, with most of the Douglas kindred to fight.

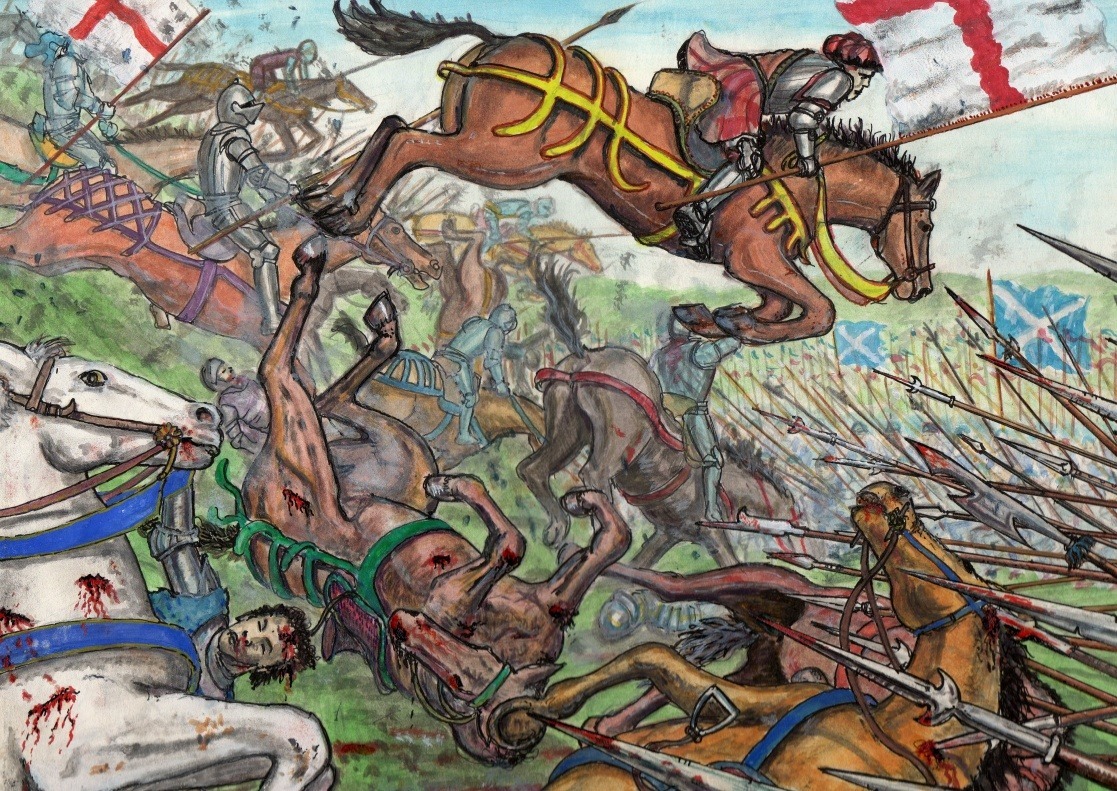

The battle actually took place near the village of Branxton, in the county of Northumberland, rather than at Flodden—hence the alternative name is Battle of Branxton. The Scots had previously been stationed at Flodden Edge, to the south of Branxton. The Earl of Surrey, writing at Wooler Haugh on Wednesday 7 September, compared this position to a fortress in his challenge sent to James IV by Thomas Hawley, the Rouge Croix Pursuivant. He complained that James had sent his Islay Herald, agreeing that they would join in battle on Friday between 12.00 and 3.00 pm, and asked that James would face him on the plain at Milfield as appointed. Next, Surrey moved to block off the Scots’ route north, and so James was forced to move his army and artillery two miles to Branxton Hill. The Scottish artillery, as described by an English source, included five great curtals, two great culverins, four sakers, and six great serpentines. The King’s secretary, Patrick Paniter, was in charge of these cannon. When the armies were within three miles of each other, Surrey sent the Rouge Croix pursuivant to James, who answered that he would wait till noon. At 11 o’clock, Thomas, Lord Howard’s vanguard and artillery crossed the Twizel Bridge.(Pitscottie says the King would not allow the Scots artillery to fire on the vulnerable English during this manoeuvre.) The Scots army was in good order in five formations, after the Almain (German) manner. On Friday afternoon the Scots host descended without speaking any word to meet the English.

The English army had formed two “battles” each with two wings. Lord Howard combined his “vanguard” with the soldiers of his father’s “rearward” to meet the Scots.[30] According to the English report, the groups commanded by the Earls of Huntly and Crawford and Erroll, totalling 6,000 men, engaged Lord Howard and were repulsed and mostly slain.

Then James IV himself, leading a great force, came on to Surrey and Lord Darcy’s son who “bore all the brunt of the battle”. Lennox and Argyll’s commands were met by Sir Edward Stanley.

After the artillery fire ended, according to the English chronicler Edward Hall, “the battle was cruel, none spared other, and the King himself fought valiantly”.[32] James was killed within a spear length from Surrey, and his body taken to Berwick-upon-Tweed. Hall says the King was fatally wounded by an arrow and a bill. Meanwhile, Lord Howard’s brother, Edmund Howard, commanding men from Cheshire and Lancashire, fought the section of the Scottish army commanded by the Chamberlain of Scotland, Alexander, Lord Home, and Thomas, Lord Dacre’s force, who had been fighting Huntley, came to assist him.

The Earl of Surrey captured the Scottish guns, including a group of culverins made in Edinburgh by Robert Borthwick called the “seven sisters”, which were dragged to Etal Castle. The Bishop of Durham thought them the finest ever seen. The treasurer of the English army Sir Philip Tilney valued seventeen captured guns as “well worth 1700 marks”, and that ‘the value of the getyng of thaym from Scotland is to the Kingis grace of muche more valew’.[

Soon after the battle, the council of Scotland decided to send for help from Christian II of Denmark. The Scottish ambassador, Andrew Brounhill, was given instructions to explain “how this cais is hapnit.” Brounhill’s instructions blame James IV for moving down the hill to attack the English on the marshy ground from a favourable position and credits the victory to Scottish inexperience rather than English valour. The letter also mentions that the Scots placed their officers in the front line in medieval style, where they were vulnerable, contrasting this loss of the nobility with the English great men who took their stand with the reserves and at the rear. The English generals stayed behind the lines in the Renaissance style. The loss of so many Scottish officers meant there was no one to coordinate a retreat.

However, according to contemporary English reports, Thomas Howard marched on foot leading the English vanguard to the foot of the hill. Howard was moved to dismount and do this by taunts of cowardice sent by James IV’s heralds, apparently based on his role at sea and the death two years earlier of the Scottish naval officer Sir Andrew Barton. A version of Howard’s declaration to James IV that he would lead the vanguard and take no prisoners was included in later English chronicle accounts of the battle. Howard claims his presence in “proper person” at the front is his trial by combat for Barton’s death.

English bill, reputed to have been used at Flodden.

Flodden was essentially a victory of the bill used by the English over the pike used by the Scots. The pike was an effective weapon only in a battle of movement, especially to withstand a cavalry charge. The Scottish pikes were described by the author of the Trewe Encounter as “keen and sharp spears 5 yards long”. Although the pike had become a Swiss weapon of choice and represented modern warfare, the hilly terrain of Northumberland, the nature of the combat, and the slippery footing did not allow it to be employed to best effect. Bishop Ruthall reported to Thomas Wolsey, ‘the bills disappointed the Scots of their long spears, on which they relied.’ The infantrymen at Flodden, both Scots and English, had fought essentially like their ancestors, and Flodden has been described as the last great medieval battle in the British Isles. This was the last time that bill and pike would come together as equals in battle. Two years later, Francis, I of France defeated the Swiss pikemen at the Battle of Marignano, using a combination of heavy cavalry and artillery, ushering in a new era in the history of war. An official English diplomatic report issued by Brian Tuke noted the Scots’ iron spears and their initial “very good order after the German fashion”, but concluded that “the English halberdiers decided the whole affair so that in the battle the bows and ordnance were of little use.”

As a reward for his victory, Thomas Howard was subsequently restored to the title of Duke of Norfolk, lost by his father’s support for Richard III. The arms of the Dukes of Norfolk still carry an augmentation of honour awarded on account of their ancestor’s victory at Flodden, a modified version of the Royal coat of arms of Scotland with the lower half of the lion removed and an arrow through the lion’s mouth.

At Framlingham Castle, the Duke kept two silver-gilt cups engraved with the arms of James IV, which he bequeathed to Cardinal Wolsey in 1524. The Duke’s descendants presented the College of Arms with a sword, a dagger and a turquoise ring in 1681. The family tradition was either that these items belonged to James IV or were arms carried by Thomas Howard at Flodden. The sword blade is signed by the maker Maestre Domingo of Toledo. There is some doubt whether the weapons are of the correct period. The Earl of Arundel was painted by Philip Fruytiers, following Anthony van Dyck’s 1639 composition, with his ancestor’s sword, gauntlet and helm from Flodden. Thomas Lord Darcy retrieved a powder flask belonging to James IV and gave it to Henry VIII. A cross with rubies and sapphires with a gold chain worn by James and a hexagonal table-salt with the figure of St Andrews on the lid were given to Henry by James Stanley, Bishop of Ely.

Lord Dacre discovered the body of James IV on the battlefield. He later wrote that the Scots “love me worst of any Englishman living, by reason that I fande the body of the King of Scots.” The Chronicle writer John Stow gave a location for the King’s death; “Pipard’s Hill,” now unknown, which may have been the small hill on Branxton Ridge overlooking Branxton church. Dacre took the body to Berwick-upon-Tweed, where according to Hall’s Chronicle, it was viewed by the captured Scottish courtiers William Scott and John Forman who acknowledged it was the King’s. (Forman, the King’s sergeant-porter, had been captured by Richard Assheton of Middleton.) The body was then embalmed and taken to Newcastle upon Tyne.

From York, a city that James had promised to capture before Michaelmas, the body was brought to Sheen Priory near London. A payment of £12-9s-10d was made for the “sertying ledying and sawdryng of the ded course of the King of Scottes” and carrying it York and to Windsor.

James’s banner, sword and his cuisses, thigh-armour, were taken to the shrine of Saint Cuthbert at Durham Cathedral. Much of the armour of the Scottish casualties was sold on the field, and 350 suits of armour were taken to Nottingham Castle. A list of horses taken at the field runs to 24 pages.

Thomas Hawley, the Rouge Croix pursuivant, was first with news of the victory. He brought the “rent surcoat of the King of Scots stained with blood” to Catherine of Aragon at Woburn Abbey. She sent news of the victory to Henry VIII at Tournai with Hawley and then sent John Glyn on 16 September with James’s coat (and iron gauntlets) and a detailed account of the battle written by Lord Howard. Brian Tuke mentioned in his letter to Cardinal Bainbridge that the coat was lacerated and chequered with blood. Catherine suggested Henry should use the coat as his battle-banner and wrote she had thought to send him the body too, as Henry had sent her the Duke of Longueville, his prisoner from Thérouanne, but “Englishmen’s hearts would not suffer it.”

Soon after the battle, there were legends that James IV had survived; a Scottish merchant at Tournai in October claimed to have spoken with him, Lindsay of Pitscottie records two myths; “thair cam four great men upon hors, and every ane of thame had ane wisp upon thair spear headis, quhairby they might know one another and brought the king furth of the feild, upoun ane dun hackney,” and also that the king escaped from the field but was killed between Duns and Kelso.

Similarly, John Lesley adds that the body taken to England was “my lord Bonhard” and James was seen in Kelso after the battle and then went secretly on pilgrimage in far nations.

A legend arose that James had been warned against invading England by supernatural powers. While he was praying in St Michael’s Kirk at Linlithgow, a man strangely dressed in blue had approached his desk saying his mother had told him to say James should not to go to war or take the advice of women. Then before the King could reply, the man vanished. David Lindsay of the Mount and John Inglis could find no trace of him. The historian R. L. Mackie wondered if the incident really happened as a masquerade orchestrated by an anti-war party: Norman Macdougall doubts if there was a significant anti-war faction.[68] Three other portents of the disaster were described by Paolo Giovio in 1549 and repeated in John Polemon’s 1578 account of the battle. When James was in council at the camp at Flodden Edge, a hare ran out of his tent and escaped the weapons of his knights; it was found that mice had gnawed away the strings and buckle of the King’s helmet, and in the morning his tent was spreckled with a bloody dew.

The wife of James IV, Margaret Tudor, is said to have awaited news of her husband at Linlithgow Palace, where a room at the top of a tower is called ‘Queen’s Margaret’s bower’. Ten days after the Battle of Flodden, the Lords of Council met at Stirling on the 19 September and set up a General Council of the Realm “to sit upon the daily council for all matters occurring in the realm” of thirty-five lords including clergyman, lords of parliament, and two of the minor barons, the lairds of The Bass and Inverrugy. This committee was intended to rule in the name of Margaret Tudor and her son James V of Scotland.

The full Parliament of Scotland met at Stirling Castle on 21 October, where the 17-month-old King was crowned in the Chapel Royal. The General Council of Lords made special provisions for the heirs of those killed at Flodden, following a declaration made by James IV at Twiselhaugh, and protection for their widows and daughters.[70] Margaret Tudor remained guardian or ‘tutrix’ of the King but was not made Regent of Scotland.

The French soldier Antoine d’Arces arrived at Dumbarton Castle in November with a shipload of armaments which were transported to Stirling. The English already knew the details of this planned shipment from a paper found in a bag at Flodden field. Now that James IV was dead, Antoine d’Arces promoted the appointment of John Stewart, Duke of Albany, a grandson of James II of Scotland as Regent to rule Scotland instead of Margaret and her son. Albany, who lived in France, came to Scotland on 26 May 1515. By that date, Margaret had given birth to James’s posthumous son Alexander and married the Earl of Angus.

A later sixteenth-century Scottish attitude to the futility of the battle was given by Robert Lindsay of Pitscottie, in the words, he attributed to Patrick Lord Lindsay at council before the engagement. Lord Lindsay advised the King to withdraw, comparing their situation to an honest merchant playing dice with a trickster, and wagering a gold rose-noble against a bent halfpenny. Their King was the gold piece, England the trickster, and Thomas Howard the halfpenny.

Casualties

Surrey’s army lost 1,500 men killed in battle. There were various conflicting accounts of the Scottish loss. A contemporary account produced in French for the Royal Postmaster of England, in the immediate aftermath of the battle, states that about 10,000 Scots were killed, a claim repeated by Henry VIII on 16 September while he was still uncertain of the death of James IV. William Knight sent the news from Lille to Rome on 20 September, claiming 12,000 Scots had died, with fewer than 500 English casualties. Italian newsletters put the Scottish losses at 18,000 or 20,000 and the English at 5,000. Brian Tuke, the English Clerk of the Signet, sent a newsletter stating 10,000 Scots killed and 10,000 escaped the field. Tuke reckoned the total Scottish invasion force to have been 60,000 and the English army at 40,000. George Buchanan wrote in his History of Scotland (published in 1582) that, according to the lists that were compiled throughout the counties of Scotland, there were about 5,000 killed. A plaque on the monument to the 2nd Duke of Norfolk (as the Earl of Surrey became in 1514) at Thetford put the figure at 17,000. Edward Hall, thirty years after, wrote in his Chronicle that “12,000 at the least of the best gentlemen and flower of Scotland” were slain.

As the nineteenth-century antiquarian John Riddell supposed, nearly every noble family in Scotland would have lost a member at Flodden. The dead are remembered by the song (and pipe tune)

“Flowers of the Forest”:

A legend grew that while the artillery was being prepared in Edinburgh before the battle, a demon called Plotcock had read out the names of those who would be killed at the Mercat Cross on the Royal Mile. According to Pitscottie, a former Provost of Edinburgh, Richard Lawson, who lived nearby, threw a coin at the Cross to appeal against this summons and survived the battle.

Branxton Church was the site of some burials from the battle of Flodden.

After Flodden, many Scottish nobles are believed to have been brought to Yetholm for interment, as being the nearest consecrated ground in Scotland.