Flyting or fliting (Classical Gaelic: immarbág) (Irish: iomarbháigh) (lit. “counter-boasting”), is a contest consisting of the exchange of insults between two parties, often conducted in verse.

Etymology

The word flyting comes from the Old English verb flītan meaning ‘to quarrel’, made into a gerund with the suffix –ing. Attested from around 1200 in the general sense of a verbal quarrel, it is first found as a technical literary term in Scotland in the sixteenth century. The first written Scots example is William Dunbar, The Flyting of Dunbar and Kennedie, written in the late fifteenth century.

Description

I will no longer keep it secret:

it was with thy sister

thou hadst such a son

hardly worse than thyself.

Like ane boisteous bull, ye rin and ryde

Royatouslie, lyke ane rude rubatour

Ay fukkand lyke ane furious fornicatour

Sir David Lyndsay, An Answer quhilk Schir David Lyndsay maid Y Kingis Flyting (The Answer Which Sir David Lyndsay made to the King’s Flyting), 1536

Ajax: Thou bitch-wolf’s son, canst thou not hear? Feel then.

Thersites: The plague of Greece upon thee, thou mongrel beef-witted lord!

William Shakespeare, Troilus and Cressida, Act 2, Scene 1

Flyting is a ritual, poetic exchange of insults practiced mainly between the 5th and 16th centuries. Examples of flyting are found throughout Scots, Ancient, Medieval and Modern Celtic, Old English, Middle English and Norse literature involving both historical and mythological figures. The exchanges would become extremely provocative, often involving accusations of cowardice or sexual perversion.

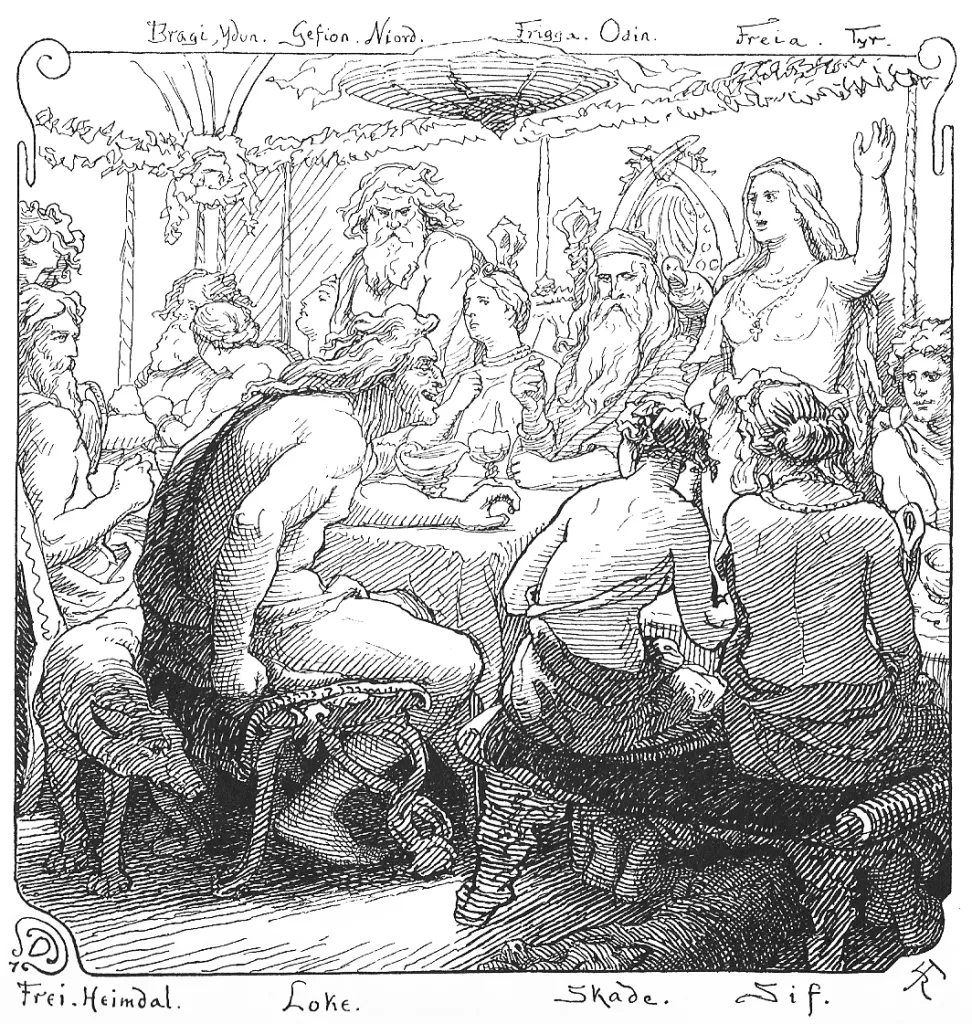

Norse literature contains stories of the gods flyting. For example, in Lokasenna the god Loki insults the other gods in the hall of Ægir. In the poem Hárbarðsljóð, Hárbarðr (generally considered to be Odin in disguise) engages in flyting with Thor.

In the confrontation of Beowulf and Unferð in the poem Beowulf, flytings were used as either a prelude to battle or as a form of combat in their own right.

In Anglo-Saxon England, flyting would take place in a feasting hall. The winner would be decided by the reactions of those watching the exchange. The winner would drink a large cup of beer or mead in victory, then invite the loser to drink as well.

The 13th century poem The Owl and the Nightingale and Geoffrey Chaucer‘s Parlement of Foules contain elements of flyting.

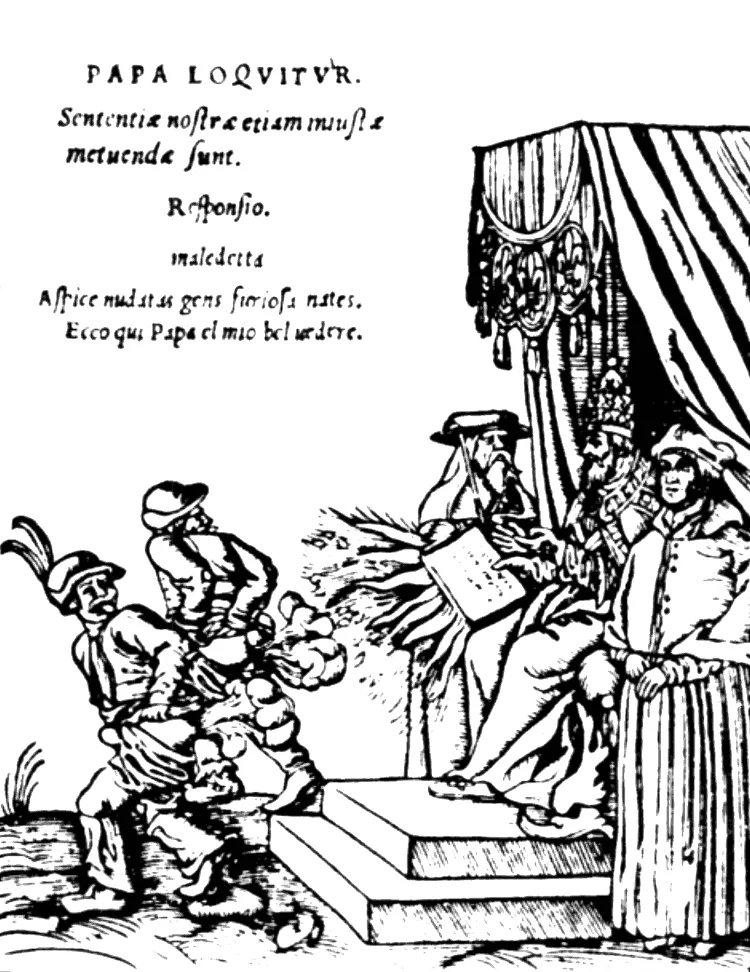

Flyting became public entertainment in Scotland in the 15th and 16th centuries, when makars would engage in verbal contests of provocative, often sexual and scatological but highly poetic abuse. Flyting was permitted despite the fact that the penalty for profanities in public was a fine of 20 shillings (over £300 in 2023 prices) for a lord, or a whipping for a servant. James IV and James V encouraged “court flyting” between poets for their entertainment and occasionally engaged with them. The Flyting of Dumbar and Kennedie records a contest between William Dunbar and Walter Kennedy in front of James IV, which includes the earliest recorded use of the word shit as a personal insult. In 1536 the poet Sir David Lyndsay composed a ribald 60-line flyte to James V after the King demanded a response to a flyte.

Flytings appear in several of William Shakespeare‘s plays. Margaret Galway analysed 13 comic flytings and several other ritual exchanges in the tragedies. Flytings also appear in Nicholas Udall’s Ralph Roister Doister and John Still’s Gammer Gurton’s Needle from the same era.

While flyting died out in Scottish writing after the Middle Ages, it continued for writers of Celtic background. Robert Burns parodied flyting in his poem, “To a Louse“, and James Joyce‘s poem “The Holy Office” is a curse upon society by a bard.[15] Joyce played with the traditional two-character exchange by making one of the characters representing society as a whole.

Similar practices.

Hilary Mackie has detected in the Iliad a consistent differentiation between representations in Greek of Achaean and Trojan speech, where Achaeans repeatedly engage in public, ritualized abuse: “Achaeans are proficient at blame, while Trojans perform praise poetry.”

Taunting songs are present in the Inuit culture, among many others. Flyting can also be found in Arabic poetry in a popular form called naqā’iḍ, as well as the competitive verses of Japanese Haikai.

Echoes of the genre continue into modern poetry. Hugh MacDiarmid‘s poem A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle, for example, has many passages of flyting in which the poet’s opponent is, in effect, the rest of humanity.

Flyting is similar in both form and function to the modern practice of freestyle battles between rappers and the historic practice of the Dozens, a verbal-combat game representing a synthesis of flyting and its Early Modern English descendants with comparable African verbal-combat games such as Ikocha Nkocha.

In the Finnish epic Kalevala, the hero Väinämöinen uses the similar practice of kilpalaulanta (duel singing) to defeat his opponent Joukahainen.

Modern portrayals

In “The Roaring Trumpet“, part of Harold Shea’s introduction to the Norse gods is a flyting between Heimdall and Loki in which Heimdall says, “All insults are untrue. I state facts.”

The climactic scene in Rick Riordan‘s novel The Ship of the Dead consists of a flyting between the protagonist Magnus Chase and the Norse god Loki.

In the Monkey Island video game series, insults are often integral to duels such as sword fighting and arm wrestling.

In Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla, in which the protagonist is a Viking themself, players can engage in flyting with various non-playable characters for prestige and other rewards.

Some see the subculture of hip hop music known as Battle rap as a modern expression, providing a platform for two individuals to poetically insult each other.

fascinating!

Thank you Patrick..