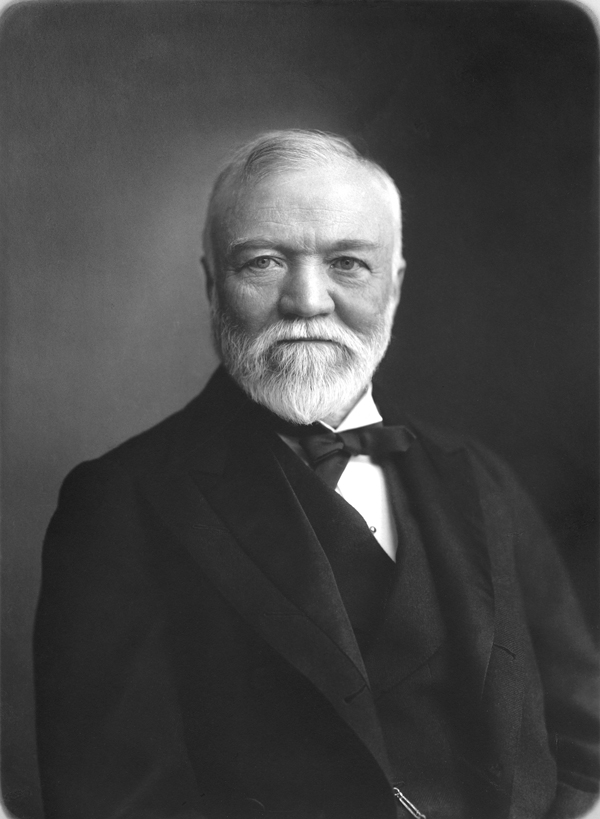

Andrew Carnegie (November 25, 1835 – August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist, and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century and became one of the richest Americans in history. He became a leading philanthropist in the United States and in the British Empire. During the last 18 years of his life, he gave away $350 million (conservatively $65 billion in 2019 dollars, based on percentage of GDP) to charities, foundations, and universities – almost 90 percent of his fortune. His 1889 article proclaiming “The Gospel of Wealth” called on the rich to use their wealth to improve society, and stimulated a wave of philanthropy.

Carnegie was born in Dunfermline, Scotland, and immigrated to the United States with his parents in 1848 at age 12. Carnegie started work as a telegrapher, and by the 1860s had investments in railroads, railroad sleeping cars, bridges, and oil derricks. He accumulated further wealth as a bond salesman, raising money for American enterprise in Europe. He built Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Steel Company, which he sold to J. P. Morgan in 1901 for $303,450,000. It became the U.S. Steel Corporation. After selling Carnegie Steel, he surpassed John D. Rockefeller as the richest American for the next several years.

Carnegie devoted the remainder of his life to large-scale philanthropy, with special emphasis on local libraries, world peace, education, and scientific research. With the fortune he made from business, he built Carnegie Hall in New York, NY, and the Peace Palace and founded the Carnegie Corporation of New York, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Carnegie Institution for Science, Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland, Carnegie Hero Fund, Carnegie Mellon University, and the Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh, among others.

Biography

Andrew Carnegie was born to Margaret Morrison Carnegie and William Carnegie in Dunfermline, Scotland, in a typical weaver’s cottage with only one main room, consisting of half the ground floor, which was shared with the neighbouring weaver’s family. The main room served as a living room, dining room and bedroom. He was named after his paternal grandfather. In 1836, the family moved to a larger house in Edgar Street (opposite Reid’s Park), following the demand for more heavy damask, from which his father benefited. He was educated at the Free School in Dunfermline, which had been a gift to the town by the philanthropist Adam Rolland of Gask.

Carnegie’s maternal uncle, George Lauder, Sr., a Scottish political leader, deeply influenced him as a boy by introducing him to the writings of Robert Burns and historical Scottish heroes such as Robert the Bruce, William Wallace, and Rob Roy. Lauder’s son, also named George Lauder, grew up with Carnegie and would become his business partner. When Carnegie was thirteen, his father had fallen on very hard times as a handloom weaver; making matters worse, the country was in starvation. His mother helped support the family by assisting her brother (a cobbler), and by selling potted meats at her “sweetie shop”, leaving her as the primary breadwinner. Struggling to make ends meet, the Carnegies then decided to borrow money from George Lauder, Sr and move to Allegheny, Pennsylvania, in the United States in 1848 for the prospect of a better life. Carnegie’s migration to America would be his second journey outside Dunfermline – the first being an outing to Edinburgh to see Queen Victoria.

In September 1848, Carnegie arrived with his family at their new prosperous home. Allegheny was rapidly populating in the 1840s, growing from around 10,000 to 21,262 residents. The city was very industrial and produced many products including wool and cotton cloth. The “Made in Allegheny” label used on these and other diversified products was becoming more and more popular. For his father, the promising circumstances still did not provide him with any good fortune. Dealers were not interested in selling his product, and he himself struggled to sell it on his own. Eventually, the father and son both received job offers at the same Scottish-owned cotton mill, Anchor Cotton Mills. Carnegie’s first job in 1848 was as a bobbin boy, changing spools of thread in a cotton mill 12 hours a day, 6 days a week in a Pittsburgh cotton factory. His starting wage was $1.20 per week ($35 by 2019 inflation).

His father quit his position at the cotton mill soon after, returning to his loom and removing him as breadwinner once again. But Carnegie attracted the attention of John Hay, a Scottish manufacturer of bobbins, who offered him a job for $2.00 per week ($59 by 2019 inflation). In his autobiography, Carnegie speaks of his past hardships he had to endure with this new job.

Soon after this Mr John Hay, a fellow Scotch manufacturer of bobbins in Allegheny City needed a boy and asked whether I would not go into his service. I went and received two dollars per week, but at first, the work was even more irksome than the factory. I had to run a small steam-engine and to fire the boiler in the cellar of the bobbin factory. It was too much for me. I found myself night after night, sitting up in bed trying the steam gauges, fearing at one time that the steam was too low and that the workers above would complain that they had not power enough, and at another time that the steam was too high and that the boiler might burst.

Railroads

memoriseIn 1849, Carnegie became a telegraph messenger boy in the Pittsburgh Office of the Ohio Telegraph Company, at $2.50 per week ($77 by 2019 inflation) following the recommendation of his uncle. He was a hard worker and would memorise all of the locations of Pittsburgh’s businesses and the faces of important men. He made many connections this way. He also paid close attention to his work and quickly learned to distinguish the different sounds the incoming telegraph signals produced. He developed the ability to translate signals by ear, without using the paper slip, and within a year was promoted to the operator. Carnegie’s education and passion for reading was given a boost by Colonel James Anderson, who opened his personal library of 400 volumes to working boys each Saturday night. Carnegie was a consistent borrower and a “self-made man” in both his economic development and his intellectual and cultural development. He was so grateful to Colonel Anderson for the use of his library that he “resolved, if ever wealth came to me, [to see to it] that other poor boys might receive opportunities similar to those for which we were indebted to the nobleman”.His capacity, his willingness for hard work, his perseverance and his alertness soon brought him opportunities.

Discover more from WILLIAMS WRITINGS

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Andrew Carnegie was definitely one of the most influential Scots… if not the most influential Scot… in world history.

The Old Scona library building in Edmonton the city in Alberta Canada where I grew up and also the oldest public library building in Edmonton started out as a Carnegie library.

Thanks, mate, yes he left a great legacy all over the World a special man, hope you are well Christopher, stay safe mate.