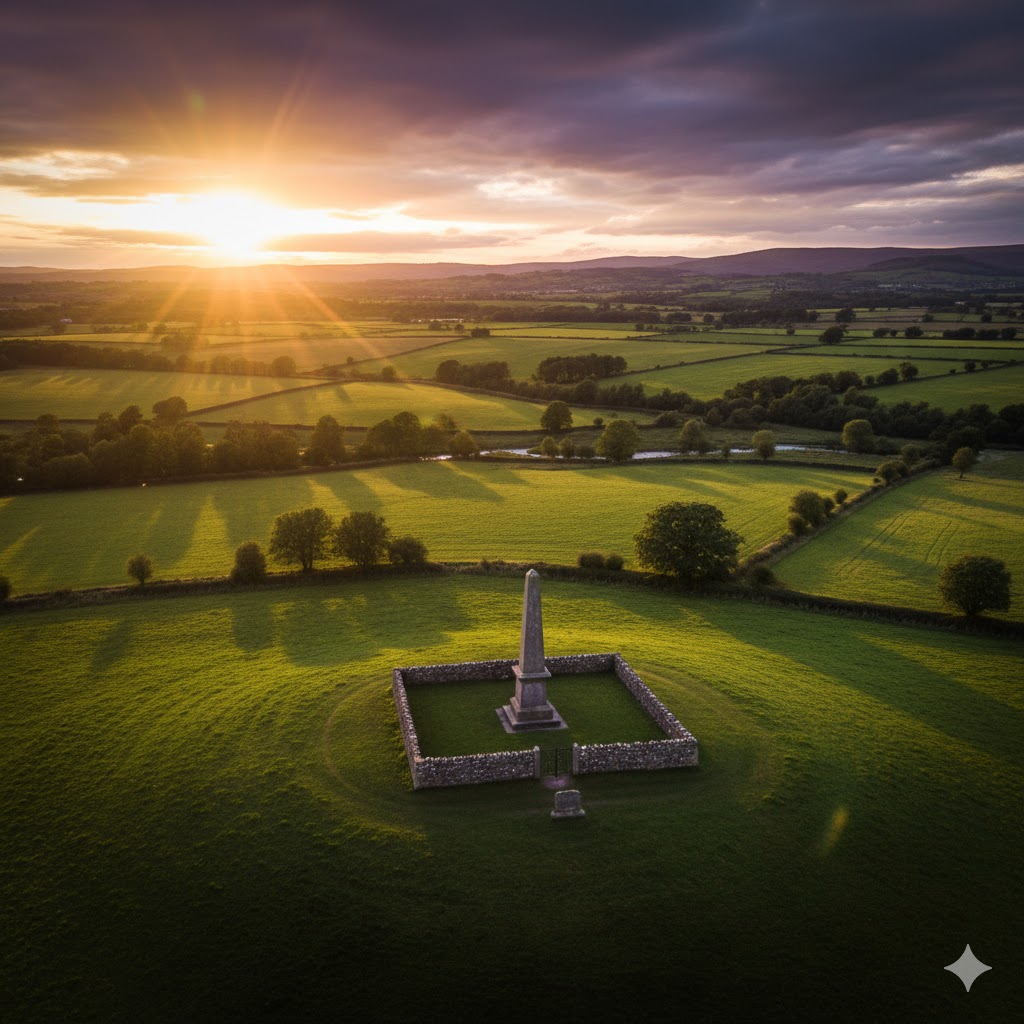

The Battle of Dupplin Moor was fought between supporters of King David II of Scotland, the son of King Robert Bruce, and English-backed invaders supporting Edward Balliol, son of King John I of Scotland, on 11 August 1332. It took place a little to the south west of Perth, Scotland, when a Scottish force commanded by Donald, Earl of Mar, estimated to have been stronger than 15,000 and possibly as many as 40,000 men, attacked a largely English force of 1,500 commanded by Balliol and Henry Beaumont, Earl of Buchan. This was the first major battle of the Second War of Scottish Independence.

The First War of Scottish Independence between England and Scotland ended in 1328 with the Treaty of Northampton, recognising Bruce as king of Scotland, but the treaty was widely resented in England. King Edward III of England was happy to cause trouble for his northern neighbour and tacitly supported an attempt to place Balliol on the Scottish throne. Balliol and a small force landed in Fife and marched on Perth, the Scottish capital. A Scottish army at least ten times stronger occupied a defensive position on the far side of the River Earn. The invaders crossed the river at night via an unguarded ford and took up a strong defensive position.

In the morning the Scots raced to attack the English, disorganising their own formations. Unable to break the line of English men-at-arms, the Scots became trapped in a valley with fresh forces arriving from the rear pressing them forward and giving them no room to manoeuvre, or even to use their weapons. English longbowmen fired into both Scottish flanks. Many Scots died of suffocation or were trampled underfoot. Eventually they broke and the English men-at-arms mounted and pursued the fugitives until nightfall. Perth fell, the remaining Scottish forces dispersed and Balliol was crowned King of Scotland. By the end of 1332 he had lost control of most of Scotland, but regained it in 1333 with Edward III’s open support. He was deposed again in 1334, restored again in 1335 and finally deposed in 1336, by those loyal to David II.

The First War of Scottish Independence between England and Scotland began in March 1296, when Edward I of England (r. 1272–1307) stormed and sacked the Scottish border town of Berwick-upon-Tweed as a prelude to his invasion of Scotland. After the 30 years of warfare which followed, the newly crowned 14-year-old King Edward III was nearly captured in the English disaster at Stanhope Park. This brought his regents, Isabella of France and Roger Mortimer, to the negotiating table. They agreed to the Treaty of Northampton with Robert Bruce (r. 1306–1329) in 1328, recognising Bruce as king of Scotland. The treaty was widely resented in England and commonly known as the turpis pax, “the cowards’ peace”. Some Scottish nobles, refusing to swear fealty to Bruce, were disinherited and left Scotland to join forces with Edward Balliol, son of King John I of Scotland (r. 1292–1296), who had been captured by the English in 1296 and abdicated.

A monochromatic impression of Balliol’s royal seal.

Robert Bruce died in 1329 and his heir was 5-year-old David II (r. 1329–1371). In 1331, under the leadership of Edward Balliol and Henry Beaumont, Earl of Buchan, the disinherited Scottish nobles gathered in Yorkshire and plotted an invasion of Scotland. Edward III was aware of the scheme and officially forbade it, in March 1332 writing to his northern officials that anyone planning an invasion of Scotland was to be arrested. The reality was different, and Edward III was happy to cause trouble for his northern neighbour. He insisted Balliol not invade Scotland overland from England but turned a blind eye to his forces sailing for Scotland from Yorkshire ports on 31 July 1332. The Scots were aware of the situation and were waiting for Balliol. David II’s regent was an experienced old soldier, Thomas Randolph, Earl of Moray, who was appointed to the role of guardian of Scotland. He had prepared for Balliol and Beaumont, but he died ten days before they sailed.

Balliol’s force was small, only 1,500 men: 500 men-at-arms and 1,000 infantry, the latter mostly longbowmen. He anticipated being joined by many Scots once he had landed. While they were underway, the Scots selected Donald, Earl of Mar, as the new guardian. Mar was an experienced campaigner and a close blood relative to David. He divided the large Scottish army: Mar commanded the part north of the Firth of Forth, while Patrick, Earl of March, commanded those to the south. Balliol had been in communication with Mar and hoped he would come over to his side with many of his troops. Knowing Mar to be commanding the troops on the northern shore of the firth, Balliol landed there, at Wester Kinghorn (present day Burntisland), on 6 August 1332.

While the invaders were still disembarking they were confronted by a large Scottish force[note 1] commanded by Duncan, Earl of Fife, and Robert Bruce (an illegitimate son of King Robert the Bruce). The Scots attacked the part of the English force on the beach, but were driven off after a hard-pressed assault by the fire of the English longbowmen and by their supporting infantry before Balliol and Beaumont’s men-at-arms could get ashore.

Scottish accounts of the time dismiss their losses as trivial, while one English source gives 90 Scots killed, two give 900, and a fourth 1,000. One chronicle, the Brut, reports that Fife was “full of shame” at being defeated by such a small force. There is no record of the casualties suffered by Balliol’s men. Mar withdrew his main force to the capital, Perth, amalgamated the survivors of Kinghorn and sent out a general call for reinforcements. Buoyed by their victory, Balliol and Beaumont’s force completed their disembarkation and marched to Dunfermline, where they foraged, looted a Scottish armoury and then headed for Perth.

English approach

The Scottish army under Mar took up a position on the north bank of the River Earn, 2 miles (3 km) south of Perth, and broke down the bridge. The Scots were enormously stronger than the English. Chronicles of the time give strengths of 20,000, 30,000 or – in seven cases – 40,000. The historian Clifford Rogers guesses they numbered something more than 15,000. Nearly all of the Scots were infantry. The English arrived on the south bank of the Earn on 10 August. They were in a difficult position: in enemy territory, facing an army of more than ten times their number in a good defensive position across a river and aware that the second Scottish army, under March, was moving towards them. The Scots were content to rest in their defensive positions, while planning to send a portion of their army on a wide outflanking manoeuvre the next day. Any attempt by the English to force the river would clearly have been foredoomed. The English may have been hoping Mar would desert to their cause, but he gave no indication of doing so. The two forces faced each other across the river for the rest of the day.

Discover more from WILLIAMS WRITINGS

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.